[[insert existing title HERE]]:

A look at paradoxical appropriation through the practice of Martin Kippenberger

INTRODUCTION:

Appropriation, Parody and the Perplexities of Paradox

‘Good artists copy, great artist steal.’

-Pablo Picasso, later stolen by Banksy

‘Art is either plagiarism or revolution’

-Paul Gauguin, written on the Franz West para-pavilion

‘Appropriation, pastiche, quotation - these methods extend to virtually every aspect of our culture.’

-Douglas Crimp

Appropriation is not a new idea, which in itself is quite humorous. The theory of appropriation has been, well...appropriated, borrowed, and reformed time and time again by each new generation of artists that move into the limelight of the current and contemporary art world. The notion of appropriation however, has developed and evolved over the years, and by now, in 2013, we have a vast discourse on the ideas around appropriation and what it means to borrow and/or copy works from art history.

Appropriation has a long history in the art world, much longer than is recognized in the majority of the discourse on the subject. Artists have always copied or borrowed whether stylistically, compositionally, conceptually, or through any other process available for art-making. Caravaggio took the hand from Michelangelo’s ‘Creation’ for his ‘Calling of Saint Matthew’, Picasso generously adapted the style of African masks into his oeuvre, Duchamp’s readymade sculptures implemented the manufacturing abilities of others, and newspaper clippings or Brillo Pad packaging became essential images for Warhol. As art history progressed, artists grasped the concept of appropriation as their entire practice. By the 1980s appropriation had become a genre in itself. Richard Prince, Jeff Koons, and most poignantly, Sherrie Levine had begun creating works solely under the pretense of appropriation setting out to discuss the notion of authorship, an idea written about by Roland Barthes in his essay ‘Death of the Author’. He writes in that text “The removal of the Author is not merely an historical fact or an act of writing; it utterly transforms the text.”

The idea that Sherrie Levine was able to pass off rephotographed Walker Evans photos as her own brings to question what does it mean to own an image or an artwork. What does it mean to be the author of that artwork and what does that particular artwork encompass? How do her photographs transform the photograph that preceded hers, or the Barthes text?

Fig. 1

The photographs that Sherrie Levine made were most definitely taken by her. (fig. 1) She made hers using the same actions that Walker Evans did when he originally took the photos: she set up a camera, pushed a button and captured the image she desired, she then developed the film and printed the image. It is her photograph. It just so happens that her subject is a photograph. In 2001 her photographs were scanned and put onto two websites by Michael Mandiberg, making them digital works, and as such, added another level of appropriation. The websites, aftersherrielevine.com and afterwalkerevans.com, offers the visitors of the websites hi-resolution images of the photographs to be printed, along with a certificate of authenticity for you to fill out and sign as the creator - or author - of the work, adding yet another layer of authorship to the original photographs. Each time the work is appropriated, a new level of absurdity is added to the situation. This absurdity allows many views and readings of the work to develop.

This action of parody is the element that has made appropriation such an interesting discussion over the years. Another example of Sherrie Levine’s which has attained a high degree of absurdity and therefore the ability to open many discussions at once is her work ‘Fountain (Madonna)’. In 1991, Levine cast an edition of polished, bronze urinals mimicking the one which Duchamp tried entering in the armory show in 1917. Perhaps Duchamp’s most famous and arguably the most influential sculpture of the 20th century, ‘Fountain’, was a readymade urinal purchased by Duchamp, the idea being that if he took a common object and put it in the art context, that simply by re-contextualizing it, it became a work of art. He appropriated the manufacturing ability of the store which he purchased it from, he then signed it with the fake pseudonym R. Mutt, gave it a witty title and placed it on a pedestal, joking that all of these things make art. In an article about Duchamp’s ‘Fountain’, an anonymous author (most likely Duchamp himself or a collaboration with Beatrice Wood and H.P. Roche) wrote in regards to the sculpture, “Whether Mr Mutt with his own hands made the fountain or not has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an ordinary article of life and placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view - created a new thought for that object.”

For Sherrie Levine to CHOOSE to edition the same urinal out of bronze, a material commonly associated with high-art, presents very contradictory readings of one work. In a catalogue for her show ‘Mayhem’, (2012), at the Witney Museum of American Art, it states that her sculpture not only points to the organic and feminine curves of the urinal, which is a gender-specific object associated with males, but that it also demonstrates that Duchamp’s once radical work has now become part of the accepted art vernacular and is no longer anything radical. Benjamin H.D. Buchloh touches on this inevitable transformation when he wrote an essay titled ‘Parody and Appropriation in Francis Picabia, Pop and Sigmor Polke’ (1982). He explains that:

“Despite their radical assault on the isolation of high art, their critique of the rarefied, auratic status imposed on objects in acquiring exchange value, and their denunciation of the obsolescence of artistic constructs . . .these works acquired a historical ‘meaning’ that entirely inverted their original intentions. They became the artistic masterpieces and icons.”

Duchamp’s attempt at creating a piece to shock, and ultimately be rejected by the art world, has failed throughout history due to art history adopting and accepting the work. The same has happened to Sherrie Levine’s works which intended to shock and confuse the art world through their destruction of the author.

It must also be said that her sculpture alludes to the worship and awe the work has gained over the years through the use of the bronze, as well as because of the two subtitles given to the work, ‘Madonna’ and the 1996 version ‘Buddha’. She understands and accepts the importance of Duchamp and his sculpture. She turns it into a kitsch object, saying that it is pastiche and common and destroys the masculinity associated with the ‘genius male artist’, but also presents it as something to hold in the highest regard and to worship in both the female and male form.

In conclusion to Sherrie Levine, it is extremely ironic that despite her works having been appropriated and almost her entire practice based on the premise of copying or taking other’s images as her own, all of her images and works are tightly copyrighted, which makes you wonder what would happen if one were to copy or appropriate a work of hers. Seems a bit contradictory, no? You see, in the 1980’s, the idea of questioning authorship was a valid one being discussed and explored by Levine and the other artist’s working around appropriation as a primary tool, but once that question was raised and explored it became insignificant and obsolete. It was proven that while it is impossible for an artist to be divorced as author of a work, or rather a work can stand without an author - even today with Tino Sehgal’s performance of perfectly executed banality and boredom by groups of generic cross-sections of society, you still know it is a Sehgal piece despite his attempts at separating himself from the work - author transference is very much a possibility, or in other cases perhaps an author addition is what occurs. In this sense, while Barthes’ desire for the death of the author is one that should still be aspired to, it is inevitable that an author of a work will always stand responsible, whether the original author or not.

Fig. 2

Something else happens to a work, its aura and the authorship of a work when it is not only appropriated but when the actual, physical object is taken and transformed. Robert Rauschenberg created the most prime example of this sort of action in 1953 he made his ‘Erased de Kooning Drawing’. (fig. 2)

After attempting for some time to create a white drawing to accompany his white paintings, he decided the best way would be to erase a drawing, but not one of his own. In his own words describing the action, Rauschenberg said “when I just erased my own drawings, it wasn’t art yet. So I thought ‘a-ha! It has to be art’”. So with a bottle of Jack Daniels in hand, he went to Willem de Kooning’s house and knocked on the door hoping that he wouldn’t be home due to his overwhelming fear of what he was about to ask of his artistic hero. De Kooning let him inside where Rauschenberg proceeded to explain his work and the predicament he faced of it not being art. He then asked if he could have a drawing of de Kooning’s to erase. De Kooning’s response explained a lot about his generation of artists and their views of the up and coming generation. He said that he didn’t like it, but that he understood the idea, and would therefore help by giving one of his drawings to erase.

He brought over a portfolio of drawings that he had been working on. Going through them, de Kooning eventually closed it up and grabbed a second portfolio containing better drawings than the first. Explaining that these drawings still weren’t good enough, he then brought out a third portfolio of his best drawings. He knew that it had to be one of his best drawings in order for this to work. He would have to truly miss it once it was gone. Additionally, he was going to make it as difficult as possible for Rauschenberg to erase it. De Kooning was at the time working on his prolific series of women which won him the notoriety and reputation by which we know him by today. It can be imagined that the drawing he chose was most certainly a working exploration of a Woman painting. He finally decided on a drawing that contained graphite, charcoal, ink, oil paint, pastel and crayon. Rauschenberg spent about a month and used around 30 erasers to complete his work.

Not sure how to title or present the work, he went to his closest friend, Jasper Johns, to ask for his assistance. Jasper Johns matted the work as it is seen today, and hand wrote the placard below which reads: ‘ERASED de KOONING DRAWING - ROBERT RAUSCHENBERG - 1953’. So then, the only things you see are the very faint remnants of the de Kooning and the words written by Johns. There is no physical mark left by Rauschenberg, only the idea of what he had done is left before you, everything else was appropriated.

This prolific work of nothing but a white piece of paper has been seen both as a purely modern drawing, working from the idea of the abstract expressionists in his attempt to draw white, and also looked at as the first look into post-modernism and the oedipal nature of the artists following pure abstraction. How is it that one work can be the perfect manifestation of the very antonymous modernism and post-modernism? It is through appropriation that this is achieved.

A peculiar happens when the context of something is altered or transformed, whether it be an idea, an artwork, a song, a text or even science. In 2006, Beti Zerovc participated in a pseudo-interview with Walter Benjamin, who died in 1940. The ridiculousness of the interviewer using (or appropriating) the name Walter Benjamin, and therefore all of his authorship is essential to the interview which argues that this re-contextualizing caused by appropriation is what allows for different and new discussions to develop; that art history (or the history of anything for that matter) comes with its own arsenal of ideas and when they are put in a new context, the meanings and discussions are able to be drastically modified, but the old meanings still exist. It only adds meanings rather than permanently changes them.

While this ability to present two contradictory views in one work is not only possible through appropriation and parody, I would argue that it is more easily achieved and more successful through appropriation. Buchloh later writes in his essay mentioned above that “Each act of appropriation is a promise of transformation...each act of appropriation, therefore, inevitably constructs a simulacrum of a double position, distinguishing high from low culture, exchange value from use value, the individual from the social.” How does appropriation attain the ‘double position’ Buchloh is talking about? I find it fitting that the words parody and paradox come from the same Greek root: para, which means alongside or beyond. When used before a suffix verb, such as -ode, meaning like or reminisce, we get the word parody, meaning alongside reminisce, or essentially to imitate or recall. When the prefix para is placed before -dox, meaning belief, we have paradox meaning beyond belief. It is through this parody that we get the paradox discussed above. It is through imitation and satire that artists are given the ability to discuss two contradictory and paradoxical opinions contained in one work of art.

Photographer Jeff Wall added to the cannon on appropriation when he wrote his essay about Dan Graham’s ‘Homes for America’, a group magazine piece about “the theme of the defeat of those ideals of rational, critical language by bureaucratic-commercial forms of communication and enforcement.” Discussing the groups appropriation and ironic parody he wrote:

“Reflected in the provocations and interventions characteristic of 1960’s Situationism, in which an unexpected and confrontational gesture interrupts the established rhythm of relationships in a specific context, and induces a form of contestation, paradox or crisis, this approach thereby exposes the forms of authority and domination in the situation, which are normally imperceptible or veiled.”

While this example is specific to the 1960’s Situationists discussed in his essay, Wall’s point can be utilized in any discussion regarding appropriation. The ‘unexpected and confrontational gesture’ of appropriation primarily induces paradox. When the context of a simulacrum is disrupted, the result is the chance to give two opposing meanings to the specific image, idea or otherwise appropriated material.

Commenting on a 1982 statement by Hal Foster about appropriation’s potential, Johanna Burton stated “The notion that appropriation might be seen as a mode of revealing language, representation and even social space to be so shape-shifting as to subsist simultaneously as both weapon and target (and thus as both subject and object) still resonates today.” It is exactly this shape-shifting ability that is central to appropriations ability to successfully discuss paradoxical themes, and is the ability which I argue is at the center of Martin Kippenberger’s practice. Like the majority of post-modern artists, Kippenberger’s practice encompasses many themes and ideas, such as travel and tourism, failure, the joke, death and many others, but through this dissertation I will argue that it is through appropriation that Kippenberger is able to successfully discuss multiple themes, and quite often contradictory themes in one work.

The following three chapters will discuss and demonstrate Martin Kippenberger’s contradictory views of himself, artists around him, and the art world and institution as an entity. It will be proven through his appropriation of art history, artists, science, architecture and concepts.

CHAPTER 1:

The Superposition of Martin KippenbergerMartin Kippenberger has been described as everything from hardworking to a jokester to a maudlin drunk to a downright nutcase. His obituary in The New York Times summarized him as “a dandyish, articulate, prodigiously prolific artist who loved controversy and confrontation and combined irreverence with a passion for art.” He truly was a deeply sincere, serious and heartfelt artist who often armed himself with the flippancy and mockery of an out of control child. Born in 1953 (interestingly enough, the same year that Rauschenberg erased the de Kooning drawing), he grew up in a home full of art and worked hard as a child to improve his ability in art-making. He took it so seriously that he dropped out of art school after getting second place for a drawing, rather than first. Still, he persevered and worked hard, using everything and everyone around him, including himself, as material for the jokes he would play in his artworks.

Self-portraits are oftentimes an accurate view of how an artist was, or at least how they wanted to be seen. When looking through the history of self-portraiture we see examples of a poor, old Rembrandt painting himself in costume to appear rich and wealthy, ‘The Desperate Man’ depicts a Courbet desperate to hold onto his own artistic freedom, Van Gogh further motivates the notion of an artist and their myth by painting himself with a head bandage in order to exploit a small ear injury and turn it into a much larger anecdote than it was in reality, and in more modern self-portraiture Francis Bacon utilizes his uncanny ability to dig into the psyche of his sitter to show himself as an anguished, yet very humble and solemn artist. How then is an artist who has so many personality traits on such radical ends of the spectrum to depict themselves in self-portraits and cover more than one aspect of their identity?

Appropriation is how.

Kippenberger famously had more self-portraits than Van Gogh. These self-portraits have allowed us to see the many roles, characters and values he sees in himself, and in cases of appropriation he was able to combine multiple, and oftentimes conflicting roles within one work. One of his most written about series is one where he painted himself as Pablo Picasso in response to an article in which Picasso and his sketches on blue hotel paper were highly admired and revered. It was this article that not only inspired/drove Kippenberger to paint himself as Picasso, but also begin his famous, life long series of drawings on hotel paper.

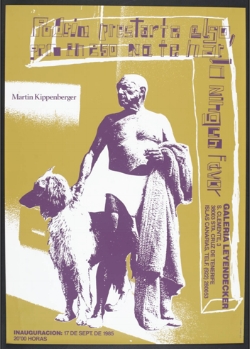

In his series, Kippenberger chose to appropriate a well-known photograph of an aging, yet still virile and masculine Picasso standing next to a dog in his underwear. Kippenberger painted himself wearing similar underwear in various poses. By 1988, when he painted these self-portraits, he had already used Picasso multiple times as a reference point in his works, including the photograph used as inspiration for these paintings. In 1985 he made a poster for a show titled ‘I could lend you something, but I would not be doing you any favors’. (fig. 3) The poster includes the title as text above the photograph of Picasso, with Kippenberger’s name beside him telling the viewer that we can borrow from art history, but we still need to make the work succeed ourselves; that it’s no easy task to appropriate from art history.

Fig. 3

Appropriating the role of Picasso, his paintings depict an aging, overweight and almost senile Kippenberger in underwear standing in odd and curious poses. One painting shows Kippenberger in his underwear melding into a shelving unit, another has him building a sculpture, and yet another has his face completely blocked by a balloon, leaving you only with the image of an out of shape old man’s body with no particular reference to whom the man could be. (fig. 4, 5) In addition, Kippenberger left all of these paintings untitled, which for him, was a very deliberate act. The punchline the title offers is always an important aspect in Kippenberger’s work, so for him to leave that information out lets the viewers know that there is nothing more to the paintings than Kippenberger depicted as an old Picasso. Or is there?

Fig. 4

Fig. 5

Kippenberger had already painted himself responding to the feelings that he was aging and becoming out of date after he was beaten up by the friends of Jenny Ratten, a regular punk performer at S.O.36, a punk club ran by Kippenberger. He painted himself wrapped and bandaged after the brutal beating. Titled ‘Conversation with the Youth’ these paintings offer a funny, yet cynical opinion of where he saw himself in relation to the youngsters of Germany.

Through the appropriation of Picasso’s appearance, however, Kippenberger portrays two views of himself: one of an aging, out of touch, decrepit old man, and the other of an artist in the strongest sense. By choosing to include the Picasso reference, he is adding to the preexisting emotion of aging and being out of date. If he takes on the role of Picasso, he takes on not just the aging Picasso, but also the successful, world-renowned, innovative Picasso. It is through the appropriation of this role that the paintings take on multiple meanings and interpretations.

On speaking about Kippenberger’s self-portraiture, one of his closest friends Albert Oehlen explained:

“What profit is there in presenting yourself in a self-portrait as good-looking? None at all, for, either no one will believe you and you make yourself look ridiculous, or they won't like you. But if you portray yourself as uglier than you are, both artist and painting benefit.”

Fig. 6

Kippenberger certainly took this idea to heart and portrayed himself as a failure over and over again in sculptures like ‘Martin, Into the Corner, You Should Be Ashamed of Yourself.’ (fig. 6) This work is a life-size sculpture of Kippenberger placed in a corner like a disciplined child. It is obvious that he is not attempting to show himself in a positive light here. Through appropriation, however, he is able to demonstrate how an artist can not only make a self-portrait which shows themself as ugly, which benefits the artist and painting, as Albert Oehlen stated, but also which shows the artist in a positive manner.

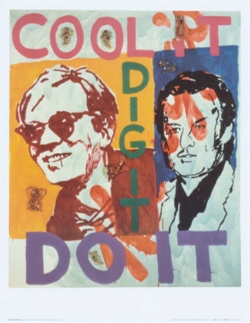

Kippenberger often employed assistants and other artists to create his paintings for him. Series of paintings such as his 1981 ‘Dear Painter, Paint for Me’ depicts many snapshots taken by Kippenberger which were then painted by a billboard painter he hired. Another series of paintings (or series of paintings turned trash, turned prints, turned installation) completed by another artists at Kippenberger’s instruction was his ‘Heavy Burschi’ (1989/90). In this work, which was initially an intended as a series, Kippenberger requested that one of his assistants create 51 paintings of various subject matters including Andy Warhol, the Ferrari logo, the Kraft logo, cartoon characters and phrases like ‘cool it, dig it, do it’. (fig. 7) The works call to mind the collages and silkscreen prints by Rauschenberg of American Pop icons and imagery that gained his association with the Pop movement. Leo Steinberg’s seminal text ‘The Flatbed Picture Plane’ reigns true with the paintings in ‘Heavy Burschi’ where a collection of images is combined with no primary hierarchy.

Fig. 7

Upon completion of the paintings, Kippenberger was unsatisfied. They weren’t kitsch enough for his taste (which gives you an insight to what he was perhaps attempting to say about Rauschenberg, Warhol and the rest of the Pop movement). Kippenberger had all 51 paintings photographed, printed and framed in order to cheapen the exhibition of the paintings. He destroyed the originals and discarded them into a ‘skip’ or a construction trash bin and put them on display in the skip with the other paintings surrounding it as one complete installation. (fig. 8, 9)

Fig. 8

Fig. 9

Multiple layers of appropriation are implemented in ‘Heavy Burschi’: the appropriation of the multiple images and logos in the paintings, the appropriation of the readymade trash container, as well as the appropriation or employment of the studio assistant, and with each of these methods of appropriation we are given a different reading of the work. His accusation of the American Pop movement of being kitschy and trash, his accusation of his own ideas being trash, or perhaps the relationship of employer to employee and the destruction of those opinions. The title adds another insight, however.

Burschi translates into English as boyishness. The title ‘Heavy Burschi’ therefore references the difficulty in keeping up the childish antics which Kippenberger often involved himself. In talking about Kippenberger’s intensity, Friedrich Petzel, who not only was once director of Capitain Gallery in Berlin where Kippenberger showed, but who also a very close friend of Martin Kippenberger said:

“He was the most intense character I have known in my life so far, and he was not easy to be around sometimes...the intensity was sometimes excruciating, so sometimes you would need to go into a spa for three days afterwards, but at the same time he was very life embracing. It’s a double edged sword, you see. If you live that life, there are certain consequences, but you would never stop.”

Upon hearing that from Friedrich Petzel, you can’t help but think of this title and this work as a quietly, honest confession of the difficulty Kippenberger felt in his career and the exhaustion he felt of having to keep up with all of the crazy decisions.

There is another form of appropriation in ‘Heavy Burschi’ that adds a whole other reading into the work. In Giorgio Agamben’s ‘Means Without End’ he discusses the human condition and the politics surrounding it. I would argue that Agamben’s chapter titled ‘The Face’ demonstrates that by Kippenberger appropriating his own work (by having them reprinted and hung) all of these possible readings of the work are accurate. Agamben argues that while all living beings have a visage or appearance, humans, because of our desire to control our appearance, are the only ones with a ‘face’, and in this ‘face’ is where truth is held. He goes on to explain that through exposition and language we are able to give a face to nature and inanimate objects. He states: “Thus the face is above all the passion of revelation, the passion of language. Nature acquires a face precisely in the moment it feels that it is being revealed by language.” He goes on to say “There is a face wherever something reaches the level of exposition and tries to grasp its own being exposed...thus art can give a face to an inanimate object, to a still nature.” In other words, when something is exposed or exhibited - i.e. Kippenberger’s own paintings being appropriated by himself - the object is given a face and given the power or passion of language and truth.

Agamben uses the example of actors in pornography. He explains that more and more, the actors are looking into the camera and confronting the voyeur’s gaze When that happens, subtleties of the human face are divulged to the voyeur. The actor has exposed him/herself as knowing they are actors. “The fact that the actors look into the camera means that they show that they are simulating; nevertheless, they paradoxically appear more real precisely to the extent to which they exhibit this falsification.”

So how does this work with ‘Heavy Burschi’ prove appropriation’s ability to speak paradoxically? By combining the original, destroyed paintings with the reprinted works, the reprinted works are being exposed as not original. They are given a face and they ‘show that they are simulating’. Therefore, they appear more real despite the fact that they are reproductions. This position of being more real and being given a face gives them the power and passion of language and truth. They hold the truth; therefore whatever they are viewed as, is therefore seen as true readings of the paintings.

A similar thing happens in Kippenberger’s ‘Orgone Box by Night’

In 1935, Erwin Schrodinger, a Nobel Prize winning physicist derived a paradox from an equation he discovered. The paradox which involved a cat inside a box would demonstrate how something can exist in two states simultaneously, essentially proving that the cat placed inside this box would be both alive and dead at the same time. The details of the experiment are as follows.

Take a steel box, and inside it place:

- Geiger counter (a device used to detect radioactive material)

- A radioactive material

- A hammer

- A vial of poison

- A cat (living)

When the following objects are placed inside the box, the experiment will take place. As the radioactive material breaks down and deteriorates in a random process (because it is radioactive) the Geiger counter will detect this and trigger the hammer to break the vile releasing the poison, subsequently killing the cat. The (knowledge of the) cat’s death, however, is only known upon opening the box, so it must be assumed that the cat is both dead and alive at the same time. This phenomenon of something existing in both states is known in physics as superposition.

In 1940, just 5 years later, Wilhelm Reich, another scientist (a psychologist this time) far less revered for his research discovered what he said to be a new form of energy which he called ‘orgone energy’. This new energy was a take on Freud’s idea of a libido, however in Reich’s version, this cosmic force could be used to improve life, kill cancer and even be used as a weapon against the Nazi’s. In order to concentrate that energy onto the body, Reich invented the ‘orgone accumulator’ which was essentially multiple layers of sheet metal, insulation and wood, creating many boxes within boxes within boxes. A person afflicted was to sit in the box naked and allow the concentrated orgone energy to heal him.

The orgone accumulators themselves have a rich history. The FDA eventually outlawed the production and sale of the accumulators and Reich was eventually convicted to two years imprisonment for violating that ruling. The orgone accumulators and literature were also sentenced to destruction by the hand of Reich and his son. Many accumulators had already been sold by that point, purchased by such figures as Sean Connery, J. D. Salinger, as well as Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg.

Fig. 10

How does this apply to Kippenberger? Well, in 1982 Kippenberger, with the help of fellow artist and close friend Albert Oehlen made a smaller orgone accumulator to house paintings of his which he felt were failures and needed improvements. (fig. 10)

Marcus Verhagen writes about the work in an article for the magazine Modern Painters. In 2006 he wrote, “This was failure squared; his rejection of the paintings hilariously compounded by the failure of the box to redeem them and by the arts’s identification with a discredited thinker.” Here Verhagen points out the humor in Kippenberger’s constant failure and self-degradation. He is saying that not only does Kippenberger point to his lack of success by discarding his paintings, but by associating himself with an ultimately imprisoned doctor he is allowing failure to seep into all aspects of his practice. While Verhagen’s point is true, failure is an obvious reading of the work, it is not the only reading, and to stop there is doing a disservice to ‘Orgone Box by Night’.

Part of the instructions for Reich’s orgone accumulator was to sit nude in order to have the least amount of physical material between you and the orgone energy. Keeping this in mind, it is as if to say that by placing his paintings in his homemade orgone accumulator, Kippenberger is exposing his paintings, leaving them naked and vulnerable. If one moves past the failure aspect of the work, it is easy to come to the conclusions that perhaps Kippenberger was using this work not only in humor but also as a sign to the exhibitionistic position that he, as an artist, puts himself in by displaying his work. It is a work just as much about his failures as it is his ability to display as an artist does. He is taking on the title of artist in the truest, and perhaps most successful sense.

Upon looking at the work as an object, again, the failure reading is not the only one available to the work. As much as the paintings inside are failures, by using them in a sculpture he is transforming them into a new and now successful work. As paintings on a wall, they may have failed in his view, but as a sculpture, it has become studied, written about and analyzed. It is now a successful work of art, so indeed, the box had the ability to transform the paintings into successes after all. It is also important to note that while many other thinkers discredited the theories of Reich, it wasn’t entirely discredited and is still studied today. Along with the people listed above as owning orgone accumulators, Norman Mailer was a notorious follower and continued to believe in the studies through to the end of his life. He has credited much of his growth and life improvement to his many orgone accumulators.

So how then is it possible for both Verhagen’s view and reading of failure which is undeniable, as well as the opposing view that in fact, the work is about success as an artist?

Superposition.

Remember the ‘Schrodinger’s Cat’ paradox? It seems perfectly suited for discussing ‘Orgone Box by Night’ not as an allegory exactly (although connotations here are not completely farfetched) but as a tool used to analyze what takes place when viewing the work and how it can both point to failure and success at the same time. In the experiment when the cat was placed inside of the box, the knowledge of the cat’s existence disappeared. All options had to then be assumed as correct. The same process takes place in ‘Orgone Box by Night’. When the paintings are placed inside the box, we cannot know for sure if they are success or failure. The context of the paintings becomes distorted with the history of everything else in the work and therefore it cannot be determined for certain what their success is. It must be assumed then that all options are true and the work exists in a state of superposition, a phenomenon of success and failure.

CHAPTER 2:

Every country has their own art history. The focus of the art-world at one particular time shifts from location to location depending on where there is a high saturation of talent and action happening, whether that production is contained in one artist make enough of a ruckus to be noticed, or a group of artists making something happen, and in other cases it might be an assortment of groups who are causing the art world to take notice. Germany went through a very long spell of being one of the focuses of the art world. Due to their history with World War II and Hitler’s position and influence to destroy the avant-garde and declare certain artists as degenerate, the post-war position of German artists was one of trying to figure out how to adjust and move past the atrocities which their country was so deeply involved. There were varying opinions of what artist’s roles were, and how they should be conducting themselves and their practices. On one side the idea of healing and moving on, and the other the notion that to move on is to forget, and ultimately repeat the past.

One thing was certain though, post-war German was a breeding ground for intellectual and forward-thinking art. Many artists were making a name for Germany in the art world. The Becher’s had an unsurpassable influence on the photography world; Joseph Beuys’ progressed the development of what would become the accepted medium of performance art as well as the notion of social artworks; Anselm Kiefer and the neo-expressionists revived the tradition of expressionist German painting; Gerhard Richter once again challenged the concept that artists are to work in one process and created simultaneously political paintings in both perfectly abstract and photorealistic style. While each of these examples come from different thought processes and generations of German art, one thing is certain, post-WWII German provided an environment for avant-garde art to thrive once again.

By the 1980s, the art world had acknowledged the importance of Germany as a new capital for intellectual and very academic contemporary art. Artists began traveling there to be part of the art scene. Artists like Richard Hamilton and Dieter Roth traveled to Berlin to be a part of what was going on. Much like the Cedar Tavern in New York in the ‘50s, a social capital emerged for artists in Berlin. The Paris Bar became that capital. Kippenberger was already a regular patron of the bar and had traded an early painting for a lifetime of free food. He was best friends with Michael Wurthle, the owner of the bar, who would later become an integral person to Kippenberger’s practice.

The bar became the hangout for the prominent artists in Germany. Its clientele included Joseph Beuys, Gerhard Richter, Marcel Broodthaers, Georg Baselitz, Markus Lupertz, Jorg Immendorff and Richard Hamilton just to name a few. Kippenberger, being the loud, rambunctious character that he was, always seized the opportunity to the Paris Bar into his stage. Along with the owner, Kippenberger spent many evenings at the bar dancing on the tables, pulling his pants down and participating in other outrageous antics.

His sister discloses in her book that the Paris Bar is where he socialized and made his reputation amongst other artists. She writes that “Martin knew that whenever he went, there would always be someone there for him, morning, noon and night, seven days a week . . . He knew he would run into someone - friends, enemies, strangers.” It was here that Kippenberger built the relationships with other artists which he would come to analyze paradoxically through appropriation.

Fig. 11

One of the works in which Kippenberger discussed those artists around him at the time was a painting he made in 1984. In this painting we see a large canvas covered in rectangular red, grey, white and yellow shapes splayed in many different angles. The paint is sloppy and quickly applied in addition to globs and streaks of a silicone gel purposefully employed to make it look cheap. The painting is reminiscent of a poor attempt at cubism by an unsuccessful, nondescript German expressionist painter. It appears as pastiche, kitsch and all-around a bad painting of contrived abstraction. Without seeing the work’s title, you are left with the same emotion instilled in too many gallery goers without an appreciation for modern and contemporary art: “my four year old could paint that” and in this case your child probably could. And then you read the title: ‘With the Best Will in the World, I Can’t See a Swastika’. (fig. 11)

What was minutes before simply a poor painting that you were certain had no meaning or skill behind it becomes quite funny because of its obvious appearance of a swastika. This sarcastic jab stands as a punchline for the painting. In his essay about Kippenberger and his ability for humor, Gregory Williams writes “In doing so, Kippenberger conveys an unmistakable sense of comedic timing.” This comedic timing is imperative to Kippenberger’s entire practice.

While this painting in accompaniment with its title is quite funny, it becomes even more humorous when you learn more about the German artists who preceded Kippenberger. He is blatantly mocking Georg Baselitz, Markus Lupertz and other neo-expressionists who claimed their paintings had nothing to do with German military imagery. (fig. 12) Referring to some paintings he did resembling military helmets, Lupertz stated that “these motifs do not have that meaning which is generally interpreted into them: it is Zeitgeist which suggests those interpretations . . . I have always seen myself as an abstract painter. That, to me, means a painter without responsibilities.” He then went on to claim that the image of helmets came to him from a film he saw in Italy, rather than the historical attachment with WWII. He said “It was really an accident. My eye was caught because I already had an artistic idea . . . If the helmets appear to be more aggressive, then that has more to do with history than with my art.”

Fig. 12

Upon learning this, Kippenberger’s painting and title becomes even funnier due to the cynicism he is projecting on the work. He sarcastically claims that “for the best will in the world, I can’t see a swastika.” The work becomes more about the neo-expressionists and their refusal to admit their subject matter than the actual swastika.

While this particular work is revered and a favorite of many lovers of Kippenberger’s practice, and while I find it quite funny myself, it lacks in its ability to discuss multiple subjects. While it can be said that he is appropriating a style in his mockery of childish, pseudo-cubist expressionism, the appropriation is ambiguous. This lack of focused appropriation makes the work one-noted, albeit, a very comical note, alas it is still only one-directional. In the fake interview with Walter Benjamin discussed in the introduction of this dissertation, the pseudo-Benjamin explains that “These authorless works based on copies have the art-history narrative confined or ‘buried’ within themselves.” Kippenberger’s painting is not a copy, and therefore lacks the full ‘art-history narrative’ needed to most effectively criticize or critique these artists. It is in cases like this that we see the importance of appropriation needed to develop this ability. A copy of a Lupertz helmet would have contained the ‘art-historical narrative’ needed to perform such a task to its fullest, otherwise viewers of the work who are unaware of this specific movement are left with an opinion of the painting that falls short of its full potential.

How then does Kippenberger’s use of appropriation successfully show his paradoxically multilayered views of other German artists? Kippenberger was ambitious in his career and strove to be the best, or at least challenge those who were already in that position. Few German artists threatened or even attempted to outdo the influence, power and importance in not only the German art world, but the entirety of the art-world to date as Joseph Beuys. Joseph Beuys was a powerhouse in contemporary art terms and the things he accomplished while working are unprecedented. It is fitting then, that Kippenberger, through his practice of appropriation saw himself in a myriad of roles in relation to Beuys. Pop culture and physics has led the world to believe or at least be entertained by the notion of time travel and a multi-timeline universe. It has yet to be achieved outside of fiction, yet through appropriation, Martin Kippenberger successfully demonstrated his ability to live in a multi-timeline universe and be Beuys’ successor, contemporary and predecessor.

Kippenberger’s admiration of Joseph Beuys was not a secret. As a conceptual title for an unmade artwork thought up for his ‘241 Picture Titles to Hire Out to Artists’ he offered the title “I’d rather enter into the obligation of a post-death legacy and become a sweaty blood sausage in the showcase for neglected Beuys research” demonstrating his desire to become part of the Beuys cannon of references, which time has shown his success in this task. Not only becoming part of the Beuys cannon but also developing and leaving a legacy of his own which Beuys is lucky to be a part of. This goes both ways.

Even with this fondness for Beuys, and his attempts at becoming successor of the position Beuys held in the German art world, Kippenberger still made actions and works which showed that he was Beuys’ predecessor, or at least he wanted to be seen as such. In 1995, two years before his death, Kippenberger released an album of music containing only three tracks of him appropriating, or in pop-music terms, covering Beuys’ recording ‘Ja Ja Ja Ja Ja, Nee Nee Nee Nee Nee’. For over an hour, Beuys repeated ‘ja ja ja ja ja, nee nee nee nee nee’, going in and out of fits of hysterics as the differences in the repetition of the phrase are exhibited to the listener of the recording and recall the monotonous and repetitious chanting of a child whining “yes yes yes yes yes” or “no no no no no”. Kippenberger then re-records himself droning the same phrase and sets it to outrageous electronic music. He offers three options on the album, his own original ‘ja ja ja, nee nee nee’ and two humorous alternatives, one specialized for adults and the other for youth, sarcastically attempting to transform the absurd recording into something acceptable for all ages. Kippenberger daringly takes on the role and responsibility of passing Beuys’ practice onto other generations by creating the album and titling it Beuys Best, not Kippenberger’s Best. He shifts the authorship to himself saying that he is an adequate musical stand-in for Beuys.

Beuys tried his hand at music, something which Kippenberger already succeeded in with his punk band ‘The Brugas’ and his management of the S.O.36 club in Berlin. Beuys’ attempt, however, was less graceful. In 1982, Beuys wrote the anti-Reagan song and accompanying music video “Sonne statt Reagan” or “Sun instead of Rain (Reagan)” playing on the false cognate of ‘rain’ translating to ‘Reagan’ in German. Beuys’ off-putting vocal performance is difficult to listen to and is only surpassed in awkwardness by his stage presence in his music video reminding us that artists should not attempt to star in music videos (which some artists today still have not learned . . . Marina). Kippenberger was in vocal opposition of the song. The ability for Kippenberger to succeed musically, but not Beuys, calls to mind a quote by Bourriaud from his essay about Deejaying in the contemporary world. He wrote: “While the chaotic proliferation of production led conceptual artists to the dematerialization of the work of art, it leads postproduction artists towards strategies of mixing and combining products.” Kippenberger as a post-modern artist has the ability to mix and combine, and ultimately appropriate materials in ways Beuys, as an artist from the conceptual generation (not movement) lacks.

Fig. 13

Further complicating the predecessor vs successor notion, however, in 1985, Kippenberger painted “The Mother of Joseph Beuys” using himself as a stand-in for Beuys’ mother. (fig. 13). In an essay on Kippenberger and Beuys, Veit Loers imagined a response by Kippenberger to this painting: “I, Martin Kippenberger, am not the son and successor of Joseph Beuys, but actually his predecessor.” Titles are everything to Kippenberger, and here the title is just as important to the work. What appears to be a painting of a woman dressed in a very motherly manner becomes an action by Kippenberger appropriating the role of Beuys’ mother as though to say, “I came before you, I made you, you are nothing without me.” In this light, the painting can be seen as an arrogant statement by Kippenberger that if he hadn’t come along to tell the world about Beuys, then Beuys would be nothing. Kippenberger then, can in fact be seen as Beuys’ successor, but because of his role as successor, he became Beuys’ predecessor.

“At another time - wanting to expose the basic antimony between art and readymades - I imagined a ‘reciprocal readymade’: use a Rembrandt as an ironing board.”

-Marcel Duchamp

The following is a tale of Kippenberger’s success in creating such a ‘reciprocal readymade’ and the result of such a work.

An even more telling example of a contradiction in Kippenberger’s practice is found in his view on the artist Gerhard Richter. If Beuys was the reigning influence in German sculpture and performance then Richter, while part of a different generation, was his counterpart in the world of post-war German painting. With a career spanning well over five decades, his influence and mark on the contemporary art world is very apparent, and it was already in effect when Kippenberger stepped onto the scene. This made Richter a viable option for exploring the complicated views one can have on the acclaimed painter. One particular Kippenberger work stands as the pinnacle example of how Kippenberger took contradictory views of artists and their practices. This one work allows for more paradoxical exploration of opinions than any other, and is perfectly balanced in presenting two completely opposing opinions. That work is ‘Model Interconti’. (fig. 14)

Fig. 14

In the late 1960‘s, Richter began working on an ongoing series of grey paintings. Grey had been used heavily in his paintings before the first Grau abstract, but once he began exploring the surface texture of these all grey paintings, he would continue to toy with that idea his whole career, painting wholly grey paintings up until 2006. The sizes, dimensions and grey value of the paintings have varied over the years, but they consistently demonstrate the artists’ ability to create different textures on the surface of the canvas. They had been shown several times, both in exhibits made up solely of his grey paintings alone, as well as other shows mixed in with works of varying styles and artists. The grey paintings’ monetary value, however, was never quite as steep as Richter’s other works, which is how Kippenberger was able to afford one in 1986.

In 1986 Kippenberger was working on an installation entitled ‘Peter’ (which will be discussed further in chapter 3 of this dissertation). As part of the work, he was included furniture both made by him as well as other artists and designers. After purchasing the Richter painting he saw another opportunity to play a joke, as it were, on the art world and its history. Rather than including the painting as just that, a painting, he transformed the work into something entirely different.

Framing the work and attaching four metal legs, he turned a painting by a revered and beloved artists into a coffee table, and not a very good one at that.

Many views of the work transpire from the simple transformation of painting to sculpture. Beginning at the essence of the work, we must analyze what Kippenberger is making. A table. A piece of furniture. Something used to decorate a room. When looking through Richter’s catalogue raisonne you will find a particular set of eight grey paintings from 1973. They are eight almost identical paintings, same size, same texture, almost same value of grey. They are each 50cm by 70cm. By adding a 5cm frame (about the size of that on Kippenberger’s ‘Model Interconti’) you would end up with a painting the size of Kippenberger’s work. It can’t be said for certain, but perhaps the painting used by Kippenberger came from this set, but either way, it could easily be determined that here, Kippenberger is pointing to the mass production of Richter’s paintings from this time and that the accessibility of the paintings is that of mass-produced living room furniture.

Looking at this work as a manufactured table, it is important to note what kind of table Kippenberger has made. He has made a coffee table. It could have been made with longer legs and been used as a work table to point to creativity and craft, or maybe a back could have been added making the painting into a chair, used for solitary purposes, but he didn’t. He created a coffee table; a place of community and gathering. A social setting where people congregate. It is a casual place of conversation, returning once again to Kippenberger’s belief in the social aspects of the art world.

As a functioning table, however, this work fails. If one were to place a cup of coffee, the canvas would do a poor job supporting it and spills would occur. A table topped in oil paint provides a difficult surface for maintenance. Coffee table books which are so ubiquitous for this sort of furniture would be too heavy and over time would destroy the table altogether. In the end, this table fails at being, well, a table.

So back to art. It is obviously no longer simply a painting. It stands on its own as a sculpture rather than a table. The simple act of placing this work in a gallery allows for it to stand as a sculpture alone, after all, this was 1987, much more difficult things had been passed off as art by this stage. The mere fact that Duchamp called a urinal art means that Model Interconti can exist as a sculpture. Although looking back at it, this work lacks a few things that ‘Fountain’ had. Richter never signed the painting, and Kippenberger never signed the table, so the author isn’t present. Duchamp dated his work, there is no date on ‘Model Interconti’, and if there were, which date would stand as the genesis of the work, the date of Richter’s painting, or the date of the transformation? ‘Fountain’ was also placed on a plinth, but the table certainly wasn’t.

Maybe the work itself is the plinth. What would this mean for the work then? By holding up paint laid on by Richter, is it supporting the claim that he is a maker and an artist first and foremost? Or perhaps since it is an empty plinth accusing Richter of having an empty, obsolete practice. Either way, if it is a plinth, then it can once again be looked at as a piece of furniture, returning to the initial position of the work. In this way, ‘Model Interconti’ becomes cyclical. This painting/sculpture/decoration/coffee table/plinth is trapped in a circle much like Penrose steps.

The title adds to this cynicism. ‘Model Interconti’ is in reference to a hotel in Berlin which went from being one of the most premier hotels in Germany to a rundown, cheap motel, and back. By the 1980s, the hotel had regained its reputation. Kippenberger is pointing out a possible, perceived model to turn things from bad to good again. Discussing Richter’s practice, Kippenberger said “He has never offered himself up, He doesn’t know an altar, only techniques.” He accused Richter of using this same sort of cheap, hotel-style model for improving art.

If this wasn’t enough, the work was further problematized when Kippenberger sold the piece. At the time of the sale, Kippenberger had not yet reached the fame that Richter had. While his prices were increasing, he did not have the success of the painter who came in the generation prior to him, and therefore the work was sold at Kippenberger prices rather than Richter prices, essentially causing Kippenberger to have lost money in the production of the work. It would have been easy for Kippenberger to re-sell the work as a Richter, however, he let it enter the market as a Kippenberger, pointing to the fact that at the end of the day, monetarily speaking, he was still less than Richter.

The work has been exhibited and shown in a number of ways. It has been shown on its own, been included in multiple retrospectives of Kippenberger, and even reunited in displays of the installation ‘Peter’. The most interesting of these, however, is the brilliant curating of Model Interconti at Museum Abteiberg in their exhibition The Collection Schürmann in autumn 2012. Walking into a square room, you are surrounded by eight, large, grey Richter paintings on four walls. In the middle stands Model Interconti staring back at the large paintings four or five times its size. (fig. 15)

Fig. 15

A range of emotions comes from this very peculiar display of the art of these two extremely important German artists. One is that of humor. You can’t help but laugh at what an absurd and ridiculous work the table actually is. What is normally regarded as a spiritual experience in the art world, being surrounded by large paintings of one artist, like a Pollock room or a Rothko Chapel, is destroyed by the table. Any seriousness is suffocated by the artist’s joke. It is a complete mockery of the artists who came before Kippenberger; a complete disregard for their influence or place in the art world. You start to wonder what would have happened if Kippenberger got his hands on these other paintings. Maybe we would have more tables and chairs from the works mentioned above. Or maybe a Carl Andre-esque dance floor could have been created by laying the paintings on the ground.

And then that question hits you again, what would have happened if Kippenberger got his hands on these other paintings, or those of the rest of the collection? That little table takes on a personality of intimidation, threatening all art history; it becomes a defiant mark rather than a joke at all and all humor is lost in this regard.

But then as you step back and view the room from afar, the table seems so small and minuscule. Humble even. Staring up at the large paintings made by the same original creator of the little table, it seems thankful for the opportunity to stand in such a place. The reverence is returned to the situation that is normally found in these romantic viewing settings, placing you once again at the beginning of a cyclical paradox created by Kippenberger.

CHAPTER 3:

Fig. 16

The Appropriated InstitutionThe French student revolts of 1968 led to an upheaval in all sectors of education and the humanities. These riots had a direct influence in the birth of the organization of the notion of institutional critique, although aspects of this practice can be seen throughout all of art history (i.e. impressionism opening their salon des refuses). The significance of institutional critique on the art world is still noted today and the discussion is far from over. What began as physical destruction of the institution or art museum construct, with works like Lawrence Weiner’s ‘36 x 36 Removal’ (fig. 16) in which he removed a 36-inch by 36-inch square out of a wall of a museum, demonstrated the disdain and violence artists were feeling towards the situation of the art world at that time. These works evolved into textual critique with essays about the topic, as well as more relational works, which included the participation of museum visitors in works like Hans Haacke’s ‘MoMA Poll’ which openly criticized Nelson Rockefeller, who was a board member at MoMA at the time. He later went on to destroy the floor of the German pavilion in the 1993 Venice Biennial, once again using destructive acts as his medium in order to confront the negative position of the art institution, this time referring to the pavilion’s history with Nazi Germany by appropriating an act performed by Hitler in the same building. (fig. 17)

Fig. 17

By the ‘80s and ‘90s institutional critique had taken many forms including purely relational works, performance, and appropriating the title of ‘institution’ and an acceptance that despite their attempts to remain autonomous from the institution, the inevitability that artists are the institution became the tool in order to critique it from the inside, as it were. Andrea Fraser’s ‘Official Welcome’ is a quintessential performance as an example of this. In this performance, she is the opening speaker at a private reception for the MICA Foundation. She reenacts famous speeches throughout art history, seamlessly blending them together, hiding the fact that they are reenactments at all. As she continues through the performance, she strips down to a bra, thong and high heels, and ends the performance by stating that “I am not a person today. I am an object in an artwork. It’s about emptiness.” Here, she literally became the work and highlighted its banality, and therefore the emptiness and uselessness of the art speeches she quoted throughout the performance.

We have seen thus far how Kippenberger, through appropriation, was able to explore multiple opinions of both himself, as well as other German artists around him. How then would he use the same function of appropriation to participate in the discussion of institutional critique, offering multiple views of the institution in his works?

Fig. 18

Kippenberger didn’t venture into sculpture until 1987. The first sculpture he exhibited was an installation of a group of furniture crammed tightly in one space. (fig. 18) The configuration was as such, that you could not see any of the sculptures or odd pieces of furniture isolated from another. The group of furniture/sculptures included remakes and references to Franz West, Donal Judd and many other artists and makers. His appropriation in this sense included a wide variety of artists for the one work, rather than just one or two, or in other words, he appropriated the art institution. Each sculpture included in the installation has its own title, and many have since been sold and displayed separate from the rest of the installation. ‘Model Interconti’ (fig. 14) was originally created for this installation, and some manifestations have included ‘Untitled’ (the one with the pens in the pocket) from his series ‘Dear Painter, Paint for Me’. (fig. 19) Another sculpture in the show is a strange, mint-colored cart on four small wheels carrying two briefcases on the front. Titled ‘Worktimer’ (which translates into German as invoicer) it stands as a very odd-looking contraption that appears to have a definitive work-related function, but upon inspection, the purpose is anything but obvious. (fig. 20) The ‘Lord Jim Lodge’ logo is on the contraption, whose motto was ‘Nobody Helps Nobody.” ‘Lord Jim Lodge’ was an artist group which included Kippenberger. Taking this into account, the work perhaps takes on the theme of the hard work it takes in a post-modern art world where you have to fight for your own name, stance and reputation. The following year, Kippenberger painted himself as Picasso building ‘Worktimer’, as well as himself as Picasso standing in a shelving unit from this installation. (fig. 4& 5)

Fig. 19

Fig. 20

As is always imperative for Kippenberger, the title provides the stepping stones in order to begin to read and decipher this work. ‘Peter (the Russian Position)’ opens up the doors needed to get lost in the labyrinth of appropriation Kippenberger has established with this group of sculptures. When combined with its title, what appears as a charity shop’s display of used furniture thrown in the middle of a gallery, transforms into a humorous mockery of not only the artists included in the installation (remembering that at times Kippenberger included one of his own paintings in the exhibition), but also a critique of the two extreme ends of the art market.

The parenthesis is a good place to start in reading the title. The word ‘Peter’ in this title has two reference points for Kippenberger. The first is made clear by the parenthesized words ‘The Russian Position’ which is often dropped in discussion of this work. Always the wordsmith, Kippenberger includes the clarification of ‘The Russian Position’ to lead you in one direction of the work referring to St. Petersburg, Russia, and more specifically the Hermitage Museum, which is located in St. Petersburg. On the front page of their website, the Hermitage Museum states that in their collection, they house “more than three million works of art and artifacts of the world culture” which they daftly attempt to display as many of those three million works as possible. Over its existence, the museum has gained the reputation of covering its walls in so much art that you can in no way view any one piece without the disruption of another work of art. It is this ‘position’ that Kippenberger is trying to place these works. He is recalling the crowded nature of the Hermitage Museum’s curatorial decisions by forcing so many oversized sculptures into such a small space. Each work juts out in front of another making it impossible to view any of the included works in isolation from the others (unless of course they are taken away from the work and put on display, divorced from the rest of the always evolving installation like was done with ‘Model Interconti’ discussed in chapter 2).

Kippenberger has placed a new context to all of the works quoted and remade for ‘Peter’. He has not only placed them in the context of a museum, but in the context of a very specific museum which has given itself the reputation of housing too much stuff, much like that of a cemetery which has been filled past capacity, withholding from visitors the well-deserved space needed to ponder over their deceased loved ones. The German philosopher and prominent member of the Frankfort School, Theodor Adorno, analyzed the purpose of the museum in his essay ‘Valery Proust Museum.’ He begins the essay by explaining that the German word ‘museal’, which translates to ‘museum-like’ has negative connotations associated with objects which are in the process of dying and are no longer of importance to the observer. He also states that the words ‘museum’ and ‘mausoleum’ have more than phonetic similarities. He states “Museums are like the family sepulchers of works of art. They testify to the neutralization of culture. Art treasures are hoarded in them, and their market value leaves no room for the pleasure of looking at them.” With this in mind, ‘Peter’ then seems as though Kippenberger declaring these works dead or dying, which are all being used for the ‘neutralization of culture.’ By giving a title referencing a museum, he has in one instant subjected all of the sculptures, and by association the works which they are appropriated from, to a perceived death. Yet when this work was first shown, it was initially exhibited in a gallery, not a museum. In this sense, Kippenberger acts as a savior for the works. He exposes their impending death and the next moment takes them out of that context and into one of a gallery, the place where works are vital and living components of a commodity-based art economy. He revives, and even resurrects the works to the life which they had previously inhabited.

I would like to add another, even more radical analysis of the work through the scope of the museum and its affiliated connotation. In his essay ‘On the Museum’s Ruins’, Douglas Crimp, one of the foremost writers on appropriation, discusses the museum and its reference to modernism and post-modernism. It is through this essay and the appropriation incorporated by Kippenberger that I feel ‘Peter (the Russian Position)’ can be seen as a critique of both modernism and post-modernism.

Beginning with modernism, the reference to the curatorial practice at the Hermitage Museum allows for a critique of the salon way of hanging art and the cluttered aspect of such practices. And as such, the works Kippenberger is appropriating can be seen as passé. Paraphrasing Hilton Kramer, Crimp explains that characterizing or referencing the salon-style claims that the art is “silly, sentimental and impotent...had the reinstallation been done a generation earlier, such pictures [or sculptures] would have remained in the museums’ storerooms, to which they had so justly been cosigned.” Kippenberger’s installation of these works which mimic the crowded hanging of a salon-style show appears to be just that, a storeroom of discarded and forgotten sculptures.

In his essay, Crimp then goes on to discuss Leo Steinberg’s “Other Criteria” and in particular the excerpt “The Flatbed Picture Plane” which is most associated with post-modernism and looked at as one of the initial uses of the term ‘post-modern’. ‘Peter’ gives a new insight into the ‘flatbed picture plane’ discussion. It may seem irrational to state that a group of sculptures can be described as a flatbed picture plane, but it is through this notion that ‘Peter’ becomes a critique on the excess of the post-modern art market, when so much work is jumbled together and begins to look similar, overdone and inauthentic.

Steinberg’s text elaborates on his idea that in the ‘50s and ‘60s artists like Rauschenberg and Dubuffet radically shifted the ability of the picture plane by placing it on its side and composing their pictures on it horizontally rather than vertically, in order to destroy any hierarchy amongst the collage of pictures and shapes. This notion is discussed in chapter one in reference to Kippenberger’s ‘Heavy Burschi’ and the similarities of those images to those of Rauschenberg’s at this time. Steinberg argues in his essay that the physical placement of production of the picture is not inherently important. What is important, however, is the psychology of that shift. He explains:

“What I have in mind is the psychic address of the image, its special mode of imaginative confrontation, and I tend to regard the tilt of the picture plane from vertical to horizontal as expressive of the most radical shift in the subject matter of art, the shift from nature to culture.”

It is exactly this action which ‘Peter’ is carrying out. While the floor which the sculptures are placed on is not tilted vertically (which would force them to slide down, crashing and breaking in one giant, jumbled mess, which Kippenberger would have most likely found brilliant), the subject matter, however, is shifting from nature to culture . . . through his appropriation. The works in their original state look just as any other work of art, created by the hand of an artist and as such, part of nature, but when they are appropriated and combined, they become references to their makers, to the art world, and ultimately change from natural objections to references of culture.

Douglas Crimp expands on Steinberg’s idea when he wrote that “although it is doubtful that Steinberg had a very precise notion of the far-reaching implications of his term postmodernism . . . His revolution can be both focused and extended by taking this designation seriously.” By taking these ideas seriously, ‘Peter (the Russian Position)’ associates this compilation of appropriated sculptures with a museum known for its overwhelming excess and therefore critiques the post-modern ideas and values set up by Leo Steinberg as a generic, manufactured, and easily copied world of excess garbage, heaped together in an arrangement which allows for no deciphering from one object to the next.

The word ‘Peter’ however, had more than the one meaning for Kippenberger, and as is often the case, the double meaning and the intended puns discombobulate the work even more through the use of appropriation. Kippenberger often used the word ‘Peter’ as an answer in place of a lack of interest, in the same way we would today use the word ‘whatever’. In the first meaning of the title ‘Peter (the Russian Position)’ Kippenberger personifies the character of a savior for the works and artists referenced, some of which he adored, and others he despised, as well as savior for himself when his own paintings are included. Then, with the second meaning of the title ‘Peter’, Kippenberger abandons all desire to save and revive these works, and instead cloaks himself in passivity and indifference to the work. This insensitive act forces the sculptures to transform back into discarded furniture by its owner. He rejects any notion of artistic value for the works, recalling the Donald Judd idea (whose furniture is included in ‘Peter’) that furniture is not art because of its functionality, or here, its failed functionality.

So in the end, what looks like a mess of strange furniture and sculptures crammed into a small gallery is actually a gesture critiquing a specific museum, modernism, post-modernism and each of the artists associated, including himself, and all this is made possible through the appropriation utilized to create the works.

If a museum is imagined in the middle of a desert, does it still exist?

This is essentially the paradoxical question posed by Kippenberger when he established MOMAS (Museum of Modern Art Syros). In this case, however, opposed to that of ‘Peter’, when Kippenberger appropriated an entire building for a museum, and therefore the whole museum construct, the discussion results in a much more positive outcome than when appropriating specific artists and artworks to critique the institution.

On a trip to the island of Syros off the coast of Greece, in the Aegean Sea, Kippenberger discovered an abandoned structure near the home of his good friend Michael Wurthle who was part owner of the legendary ‘Paris Bar’ in Berlin talked about in Chapter 2. The sight of the abandoned structure struck a chord in Kippenberger, and he knew something had to be done with the building. (fig. 21, 22)

Fig. 21

Fig. 22

Echoing and parodying the post-Fordist forms of immaterial labour and a capitalist museum structure, Kippenberger founded MOMAS and designated himself director, manager and chief curator. MOMAS would find its home in this abandoned building. From the onset, many Kippenberger-esque problems, or jokes arose, depending on which way you look at it. The discovery factor of the building in which MOMAS was to be housed recalls the readymade idea first invented by Duchamp. Kippenberger chose to appropriate already existing architecture rather than construct his own building. In the world of institutional critique, architectural appropriation was in no way a new idea. Lawrence Weiner removed a fragment of a wall from an existing building, Gordon Matta-Clark (the Godson of Duchamp) appropriated a derelict house to be cut in half and Richard Wilson had already made many extensions of buildings by 1993 when Kippenberger founded MOMAS. Here, however, Kippenberger did not choose to destroy the building, which resembles the Parthenon, and therefore could already be associated with the history the Parthenon has to offer, i.e. an ancient temple for worship insinuating that MOMAS is a sacred and religious site. Instead, he chose to preserve the life of the building and only transformed its context. Mirroring the techniques of Duchamp, Kippenberger gave his readymade museum a title, asked for artist’s participation, sent out invitation cards and held openings despite the fact that the museum was not a reality. In her essay ‘MOMAS: The Unlikely Museum’, Katerina Gregos explains “MOMAS, of course, was not a real museum - on the contrary it was more of a virtual, imaginary museum . . . The museum did not have walls, a collection, nor anything in the way of tangible, material objects.” Michael Wurthle also stated that the audience of the museum was no larger than 9-11 people. While there were a few works shown at MOMAS, it is in this sense which the notion that Kippenberger created a post-Fordist model of a museum reigns all the more true, considering he did not employ people with material jobs, nor did he hardly employ material artworks for the conceptual museum, foreshadowing what we have seen come about in the age of the internet with online art fairs, virtual art shows, purely digital works and even AmazonArt which is running as an auction house functioning solely online.

Fig. 23

The lack of participation and attendance at MOMAS begs to be analyzed as another form of Kippenberger as a failure. He built his first MetroNet station near the museum in order to open up the site for tourism. (fig. 23) MetroNet was a project conceived in romantic dreams and constructed on a foundation of failure. Kippenberger produced a series of metro or subway stations in remote areas of the world in order to provide transportation across the globe, but as is so often the case with Kippenberger, the idea was an obvious failure from the beginning and quickly turned into a series of jokes. A MetroNet station in Syros for MOMAS, one in the Swiss Alps, one at Documenta10, which would allow attendees of Documenta to easily travel to MOMAS, one in the middle of a lake, forcing you to inconveniently travel by rowboat in order to partake in the convenience of MetroNet, and even a portable MetroNet station which would enable you to travel from where ever you were. The series brilliantly peaked when Kippenberger was offered to display one in a gallery, which would be the only place these failed metro stations would have any validity, through the manifestation of sculpture, but the gallery doors were too small for the large structure to fit through. Kippenberger advised the gallery to crush the station in order to force it into the gallery setting, once again pointing at the failure of MetroNet to even exist comfortably as an art object. (fig. 24)

Fig. 24

The MetroNet series screams the idea of failure, but by combining it with the appropriated building for MOMAS and the concept of the museum, the work in conjunction with MOMAS transforms into a romantic, idealistic dream of what could possibly be an interconnected art world.

The works that were actually foreseen at MOMAS were mostly immaterial and conceptual in design. From Huber Kiecol’s first piece there, in which he declared a neighboring building his work, to Ulrich Strothjohann declaring readymade concrete pipe in front of MOMAS would be his work, which subsequently was covered up by construction, not even allowing the few visitors of the museum to see the idea of his work. Each exhibition, however, had a title and invitation sent out, just as a real museum operates. Just as he had done with his punk club S.O.36, Kippenberger produced a social setting as a work rather than a physical object, reiterating his relation to Joseph Beuys, and adding to the discourse of relational aesthetics which was being explored in the ‘90s by artists like Liam Gilleck building social spaces within the gallery and Rirkrit Tiravanija serving pad thai in 303 Gallery as his exhibition.

Although MOMAS lacked any material goods, or even a proper structure, it succeeded on many fronts. While the ruins aspect of the space allows for a consideration into the concept of a preempted failed attempt to create a museum in a remote and nearly impossible setting, the format it proposed as a purely conceptual and imaginary museum still stands as a symbol today of what possibilities exist for projects like this. In closing her essay, Katerina Gregos writes “Perhaps the most significant aspect of MOMAS is its importance as a conceptual project, its symbolic potency, the kind of power it exerted and continues to exert on the mind, and the fascination it engenders in our imagination as pure concept.”

CONCLUSION:

Kippenberger’s Practice Through HindsightSince his death in 1997, Kippenberger has been exhibited, written about and discussed in all facets of the art world, and despite his dislike of the notion of retrospectives, multiple retrospectives have been put on in dedication to his practice. Just as his work incorporated appropriation to discuss contradictory and oftentimes confusing readings of pieces, the same can be said for the art world as it now looks at Kippenberger’s body of work in hindsight.

A curator’s material is artwork made by the hand of artists, not the curators themselves. In this sense, each time a curator puts on an exhibition, they are appropriating those artworks included and recontextualizing them in the same way an artist appropriates a theme, theory, text, science, other artwork, music, etc, into their artwork. Because of this, the same thing occurs with each new context a work of art is placed in, and as such, oftentimes contradictory views are displayed as a result of the appropriation the exhibition subjects the artworks to.