it’s the thought that counts

- an essay on ideas as art -

Think 2500-3500 words on conceptual art.

End Notes:

After conducting much research for this essay and getting a good sense of what ideas as art meant, I had concluded that the best way to demonstrate what I had learned would be through submitting instructions, and instructions alone, as my text. I wanted to allow you as the reader to create the paper in your head, not as a satirical or insulting way, but because I sincerely felt that it was the best example to teach what I had learned.

I spent quite a lot of time figuring out just how to word the instructions and how to format the essay in order it to have the most success standing on its own as a text about conceptualism. I finally settled on the three lined essay above, deciding to include the blank pages to act as a foundation to let you as the reader formulate the essay within your mind.

My opinion of the subject was that yes, indeed, ideas could stand as art. After some time however, I began to doubt in my essay as a substantial instrument in representing what I had learned. I didn’t feel that it would fully accomplish all that I had wanted. It needed more than just blank pages to think about. The idea alone wasn’t enough.

This epiphany changed the entire aim of my essay. I no longer believed Sol LeWitt’s statement that “Ideas alone can be works of art.” (1) It wasn’t enough to rely on my instructions. Something had to be added to help validate them.

No artist has every been able to walk into a gallery or museum and say “so I was thinking the other day. Now give me money.” And no artist has ever been to validate an idea with out first making and object or saying the idea aloud. A viewer needs more than the assurance of the artist that they had an idea. We don’t go into galleries to listen to artists tell us that they think and have ideas, and thats it. Art is something more. Art begins with an idea, but is not an idea alone.

All art, in essence, deals with ideas. Every piece of art had to evolve from a spark of thought in someone’s mind. The cave paintings in Lascaux started first as an idea in someone’s head. Degas had to think “I want to paint dancers” and Warhol had to decide in his mind to duplicate a can of Campbell’s soup over and over. No art can be created without an idea in the beginning. Even artists like Agnes Martin, who claimed to work solely from her subconscious, eliminating all thoughts and ideas still had to decide to work that way in the first place. She had to have the idea to work from her subconscious before actually doing it.

The Fluxus group is the first time the word concept is used to describe a work, but it isn’t until the late 60’s that artists decide to explore solely the notion that ideas, and nothing more can be art. Prior to this time, the art world was heavily saturated with artists who focused entirely on the visuality of a piece. Much like the political situation at the time, the art world in the late 60‘s took a turn for the intellectual. Academic thinking and philosophy began to take precedence over being content with the condition of the world. Artists became more intellectual in their work, rather than emotional or psychological. Much like the shift from the Baroque to the Neo-Classical in the 16th century, the late 60’s restored a focus on the mind rather than the heart.

The art history world has identified the movement that emerged from this renewed intellectualism as Conceptual Art. The main focus of conceptual art was to analyze the importance of the idea as a singular thing. They weren’t interested simply in the idea as a part of art, but rather, how far could notion of idea as art be pushed. This exploration raised many questions about the very essence of art.

Where does an artwork lie?

Is the work in the presentation? The exhibition? The catalogue?

Is it in the frame or stretcher bars? Or the maquette to form a sculpture?

Or perhaps an art work lies in the paint or graphite or ink or glue? In the steel or concrete or clay?

Is an art work more than a date or signature or title?

When is the work made? Upon conception of the idea maybe? Or when the first mark is made, or when the last mark is made?

Is the work finished when it is shown, or sold, or hung in a home?

Is it art when it is in a museum or book?

Can it be art outside the gallery or outside the institution?

Can a work be made more than once? And if so, then is it one work or two? Has the work become a series of identical works?

“Is when Rauschenberg looks an idea?”

-John Cage (2)

Samuel Beckett’s play Waiting for Godot raises many questions about time and dates. Many of these same questions can be looked at in accordance with the art world of the late sixties and leading into the seventies. In a review of the play, Vivian Mercier said about Beckett “he has written a play in which nothing happens, twice.” (3) This idea is fascinating, especially when looked at through conceptualism. Artists selling instructions for their works, rather than the works themselves means that a work can exist more than once. These works that never happen by the hand of the artists in fact break the most fundamental rules of time. If an idea is a work alone, then the result of that idea should stand as evidence of the work. But what happens when the result is repeated, is the idea duplicated? Does the work now exist in multiple forms?

The Greek myth of Theseus’ Ship has a remarkable parallel to these questions that seem to form from the new and changing art world in the late 1960’s. In this myth, the ship of Theseus needs to be repaired, so they fix it. Something new breaks, so they repair it again. Every part of the ship breaks, and eventually every part of the ship is replaced. Each nail, every plank of wood; the stern, the bow, the rudder; it is all substituted with a new part. At the end of the restoration of his ship, Theseus asks the question of whether or not it is the same ship. If everything is new, is it the same ship you started with? And if so, what happens if you put all of the old pieces together? Do you have a new ship, or are you left with the same ship, twice?

What does this mean for conceptual art? If the idea is the work, and can be repeated or duplicated, where is the work? Is it in the instructions for the work, or is it maybe in the evidence and documentation of the idea?

The last sentence in LeWitt’s Sentences on Conceptual Art says “These sentences comment on art, but are not art.” Earlier in the same text, LeWitt states that “All ideas are art if they are concerned with art and fall within the conventions of art.” (4) In 1972 John Baldessari turns these two statements against each other in his film Baldessari Sings Sol LeWitt (5). He puts LeWitt’s words into the conventions of art simply by making a film of them. His lackluster attitude throughout the film mirrors the rigidity and intellectuality of the time. This turns these sentences into art which contradicts the very essence of the last sentence in the text. He resurrects the questions first posed by Duchamp’s Fountain.

Sol LeWitt explored the notion of instructions as art more in depth than possibly any other artist. His ability to coherently and concisely explain the location and essential elements of a line or a mark is unmatched. His instructions were so perfectly explored that without mistake, when followed, you would end up with the same drawing as he had intended, with little room for error or variation. Concerning the method of planning and instructing a drawing, he said “To work with a plan that is pre-set is one way of avoiding subjectivity. It also obviates the necessity of designing each work in turn. The plan would design the work.” (6) He later goes on to explain that the artist selects the rules, and the rules then govern the process of making the work. The less choices made in the production of the work, the better.

LeWitt stays very loyal to this thinking throughout his whole career as an artist. His works therefore, always have a very academic and intellectual feel to them. This is not to say, however, that there is not beauty in the work. There is something so profound and yet elegant in his ability to simplify and elucidate the creation of a line to a sentence or paragraph.

Douglas Huebler’s work more poignantly illustrates the attempt made at this time to allow and idea stand as a work of art, as his works are only evidenced through his instructions and documents of the idea at hand. He is best known for two types of work; his photographs and his maps of earthworks. The most applicable series of work that pertains the the subject of ideas as art was his series titled: “Everyone Alive” (7) in which he attempted to photograph every person on earth. The idea of photographing every person on earth has much power than the images themselves. The grander and enormity of an idea so impossible induces a feeling of beauty and wonder. It allows you to contemplate the notion of ideas as art. The physical evidence of the idea is far less aesthetic than the idea itself, but this is not to say that the photos are not still an object looked at and targeted as the work of art. Huebler did not allow the idea to stand simply on its own as a work of art. Rather, he took photos to prove that the idea existed. He needed to create a physical thing to stand in place of the idea. Here, the idea finishes the photo series, but it still relies on the photos to be art. He got close to fulfilling LeWitt’s statement that ideas alone can be art, but he did not successfully prove this notion correct.

Another work of Huebler’s that comes close to achieving this is his series of proposed earthworks in which he called ‘location pieces.’ (8) He created maps, drawings, photographs and detailed instructions to explain the idea behind the work. There is always an object presented at the end of the idea, rather than leaving the idea to stand on it’s own. The idea leads to a chain of events, which is something that LeWitt touches on in his sentences on conceptual art. He says “they are a chain of development that may eventually find some form.” (9) Many of Huebler’s ‘location pieces’ were so large in scale and thought that the actual production of the work was impossible, once again leaving the idea to be the work itself, but even in these instances, he still had the maps, drawings, photographs, texts and other documents to validate and commodify the idea as a work of art. Never did the idea stand as the work alone.

The presentation of these works is stunning, which brings up more questions of the validity of LeWitt’s statement. If an idea can stand alone, why put so much effort into the aesthetics of the idea; why make sure that the presentation of the instructions looks nice at the end? If the idea is the work, why not leave it at that and trust that it will be accepted as a work of art? So much of the conceptual art works are very beautiful sets of instructions and documents. These artists focused on making sure their ideas were shown as aesthetic objects. They put effort in the creation of the object as a work, focussing more on the object as evidence of the idea rather than the idea itself. That’s not to say that there is anything wrong with the focussing on aesthetics, but when to pass a work of as simply and idea, the focus on aesthetics becomes arbitrary.

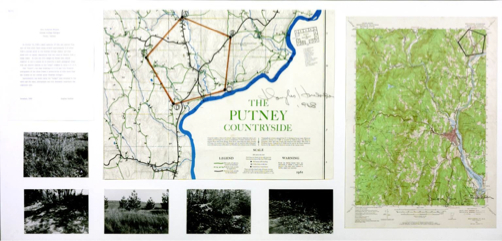

Two perfect examples of this are in Sol Lewitt’s Wall Drawing #232 and Douglas Huebler’s Site Sculpture Project, Windham College Pentagon, Putney, Vermont. Sol Lewitt’s wall drawing is owned by the SFMOMA. (10) This, in itself is very intriguing. The museum did not purchase the drawing, but the instructions for the drawing. Sol LeWitt as an artist making a living on his art knew he had to make something that looked like it was of value. His instructions for this drawing, therefore, very carefully constructed. He writes them out in a perfect square, (fig. 2), concentrating on the accuracy of his words to communicate the idea and the process established to create the work. He makes sure that the paper containing these instructions looks like it is worth something. He does not trust the idea itself, so he relies on the aesthetics of the instructions to validate the importance.

Similarly, and even more uniquely, Huebler’s documents for his site sculptures, which were made in 1968, are presented as a beautiful object. These documents, as one object, are titled Site Sculpture Project, Windham College Pentagon, Putney, Vermont (11) and are the documentation of an event made by Huebler. They are framed together in a very geometric manner almost referencing work by Mondrian or van Doesburg. (fig. 3) The composition of the presentation is something to be admired and rivered simply as an object alone. You begin to forget that the work is even an idea at all. This makes it easy then, to be looked at as a valuable commodity, rather than an artistic concept.

In my research, I came across an interview with Ed Ruscha talking about conceptual art. He mentions in this interview that he believes the purest form of conceptual art resides in a piece by Lawrence Weiner which never even existed outside of the simple idea. (12) This was astounding to me. I thought I had finally found a work that simply resided as an idea.

I delved into research to find more about this piece titled An object tossed from one country to another. I learned that this piece did not exist simply as an idea, in fact it was part of an exhibit put on by Seth Siegelaub. The show was a collection of works by 31 artists. Each were assigned one day in March, 1969 to create a work. Along with Weiner’s work, the show included such works as Claes Oldenburg’s Things Colored Red on the 24th of March and Robert Morris’ submission of his home address as his work on the 22nd. (13) The catalogue for this exhibition is a collection of the various ideas conceived by the artists, many of which pieces - Weiner’s piece included - did not develop past the conception. So it could be said that this was an entire exhibit of ideas as art, but the simple fact that it was an exhibit at all and that these ideas exist in writing in the catalogue means that they became an object, and once again did not stand simply as ideas.

And if you want to be really critical, once an idea is said, it can be categorized as a performance work, and more than just the idea. The idea cannot stand alone as the work of art, it always needs some other object or medium to validate it as such.

It is perfectly apparent that the art world had radical changes in the late 1960‘s and 70‘s. The student riots in Paris paved the way for more intellectual thinking in all aspects of the world. Conceptual art bloomed from this shift, and permanently affected the art world to come. It is impossible to argue that the conceptual art movement was not valid, which is in no way the aim of this essay. This essay is however, trying to argue that perhaps, this movement was a little to grandiose in their assumption that an idea can be a work by itself; that a simple thought or concept could be construed as art with nothing to stand as evidence of the thought.

Work Cited

Cage, John. ‘On Robert Rauschenberg, Artist, and his Work’, in Art in Theory 1900-2000 (Massachusetts, 2003, Blackwell Publishing) New Edition, p. 734

LeWitt, Sol. ‘Paragraphs on Conceptual Art’, in Art in Theory 1900-2000 (Massachusetts, 2003, Blackwell Publishing) New Edition, p. 847

LeWitt, Sol. ‘Sentences on Conceptual Art’, in Art in Theory 1900-2000 (Massachusetts, 2003, Blackwell Publishing) New Edition, p. 850

Primaryinformation.org “Seth Siegelaub Archive.” Primary Information. October 29, 2012. http://www.primaryinformation.org/index.php?/projects/seth- siegelaub-archive.

SFMOMA. “Sol LeWitt Wall Drawing #232.” Accessed October 30, 2012 http://www.sfmoma.org/explore/collection/artwork/27141

Smith, Roberta. “Douglas Huebler, 72, Conceptual Artist.” The New York Times, July 17, 1997. http://www.nytimes.com/1997/07/17/arts/douglas-huebler-72-conceptual-artist.html.

Tate Modern. “Douglas Huebler Artist Biography.” Accessed October 30, 2012. http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/douglas-huebler-1320/text-artist-biography

Mercier, Vivian. "The Uneventful Event." The Irish Times, February 18,1956, p. 6

YouTube.com. “Baldessari Sings Sol LeWitt.” google.com. March 4, 2007. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q6eSfKeJ_VM

YouTube.com. “Conceptual Paradise Trailer.” google.com. July 10, 2007. http://www.youtube.com/wathc?v=Tb100kzsAsY.