April 11 - Walking Notes

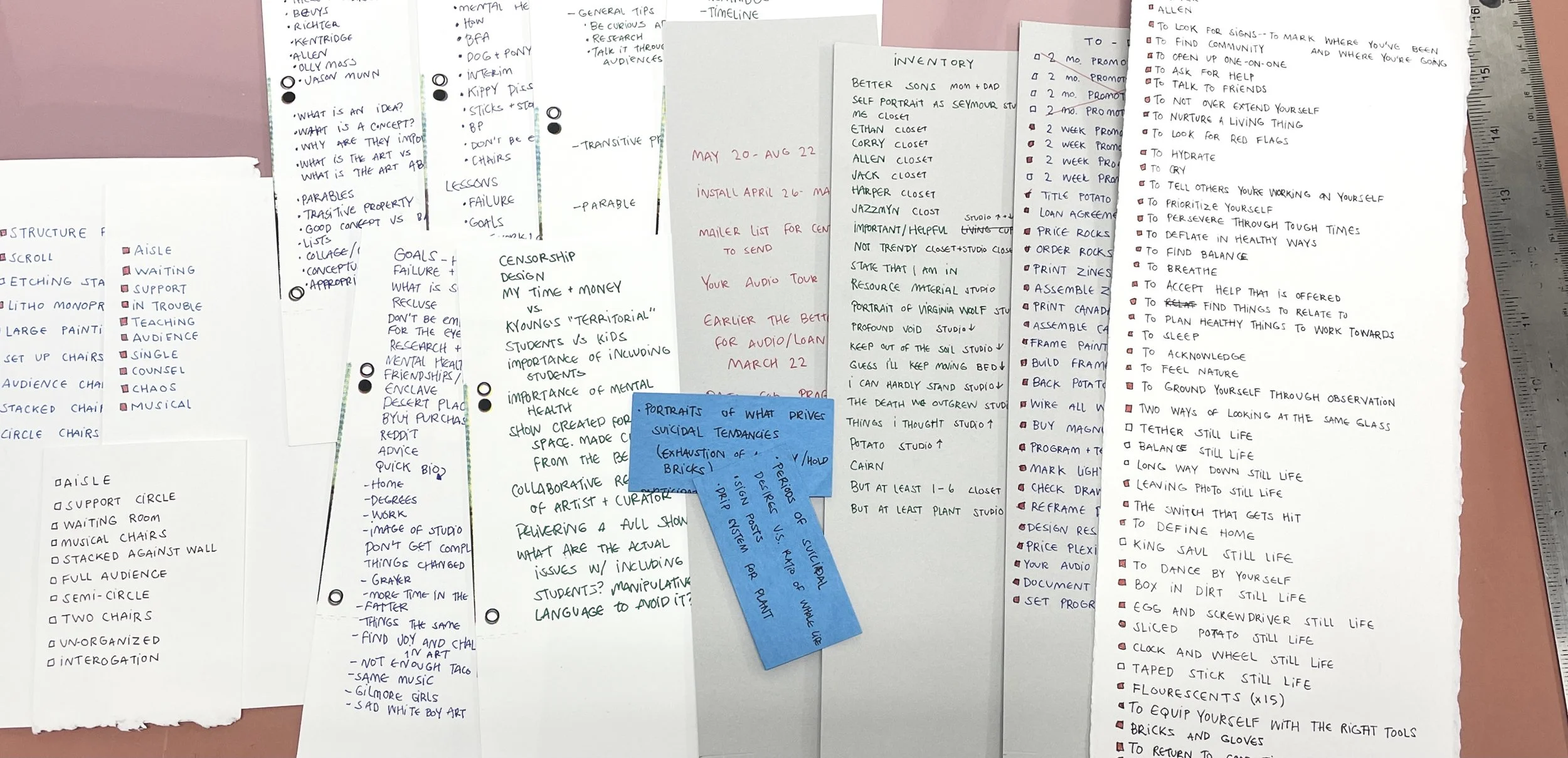

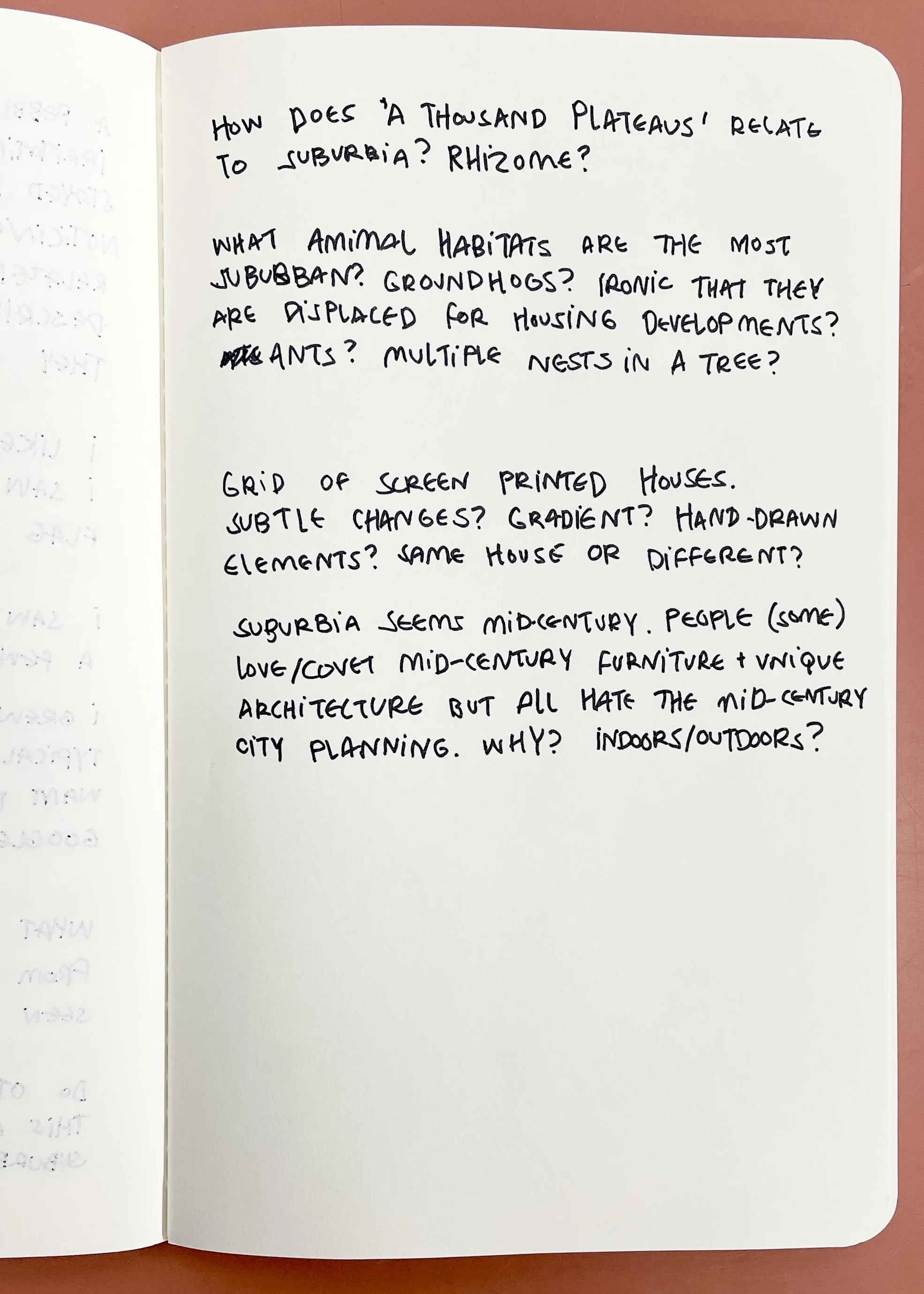

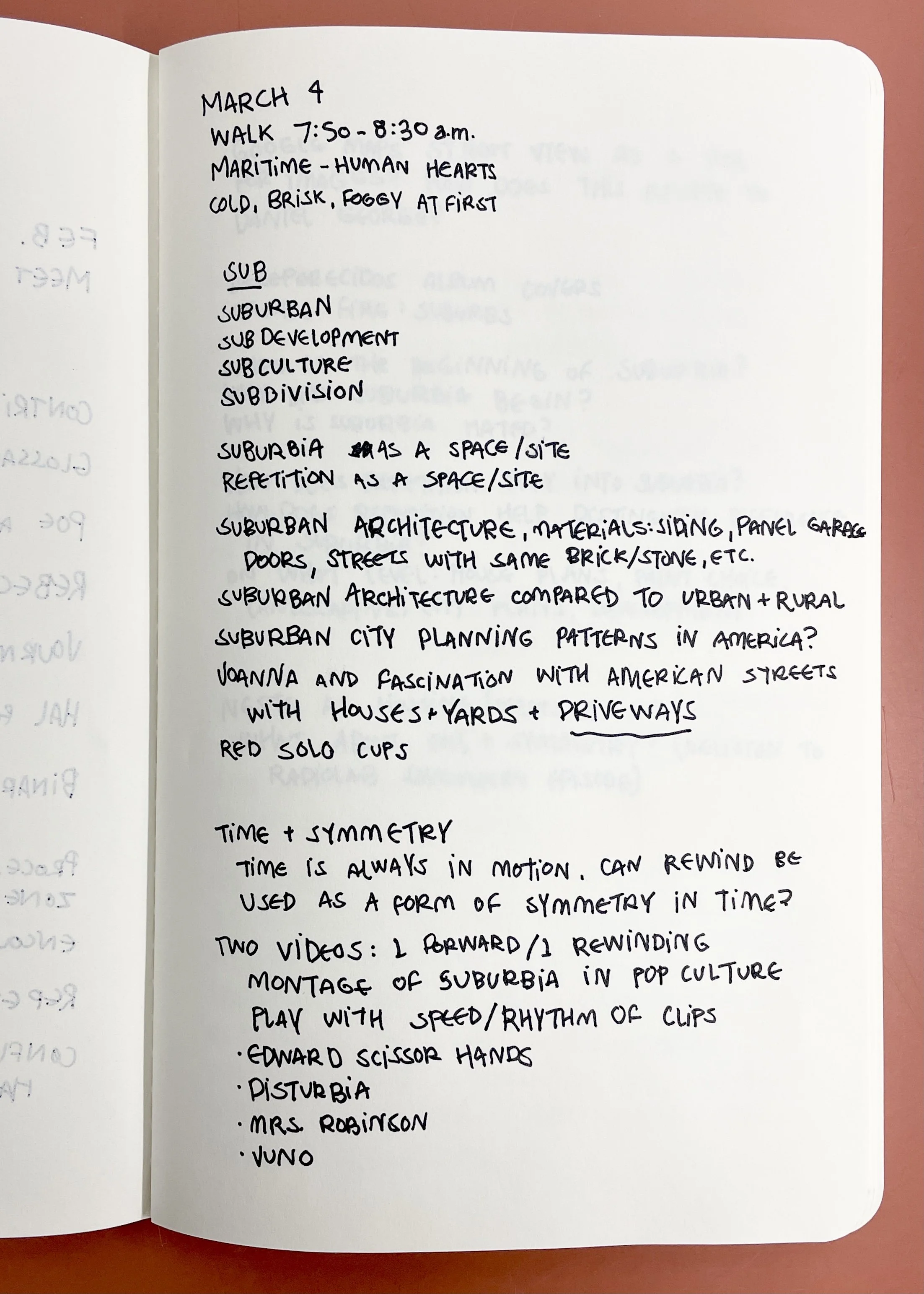

Lists as Sketching

Lists are a key component of my art practice and I only recently became aware of this. Lists are an essential part of trying to keep a sense of control and overview of my life when things start to feel too chaotic and scattered in my brain. This function of chaos control was how lists first found their way into my practice many years ago, but since then lists have evolved in their role in my practice.

A list of lists:

To-do lists (completion mandatory)

To-do lists (permission to leave list incomplete)

Ideation lists

Inventory lists

Individual piece progress lists

Notes as lists

Art opportunities lists

Submission tasks lists

Exhibition packing lists

Exhibition planning lists

Exhibition artwork lists (hybrid inventory and to-do lists)

Presentation or artist talk brainstorm list

Presentation or artist talk outline list

Cv

The shape of my lists has become a good indicator of how a body of work or an exhibition is progressing. When I start making good, long lists I know my ideas are starting to come together and there is some synthesis taking place in my concepts. When those lists start to get rewritten and whittled down, I know I’m nearing the final set of works in the show for that particular time. It would benefit me to eventually analyze where lists reside in time in my practice, when certain lists are made, and what that may or may not represent about my work, i.e. ideation lists at the very beginning and the Cv as a running list of things in the past.

Many of the lists in my art practice are used as project management to-do lists. It took many years to come to terms with the fact that my to-do lists don’t all have to be checked off. This is a permission only granted to lists in my art practice (life to-do lists continue to have the requirement for completion). Permission to not complete an art to-do list only came from realizing that the idea still existed regardless of if I made it at that time.

Because of this, I don’t discard my lists.

And through the recent realization of the importance of lists in my practice, I am starting to view the process as something more akin to sketching. These lists are the closest thing I have to a consistent sketchbook practice currently. (I want to one day unpack the pressure I feel to keep a traditional sketch practice.) They are a form of sketching concepts through language rather than image. And like any consistent sketching practice, some entries take a more final form than others. Some entries are revisited later and reworked. And some entries are completely abandoned, only to live in their original list/sketch form.

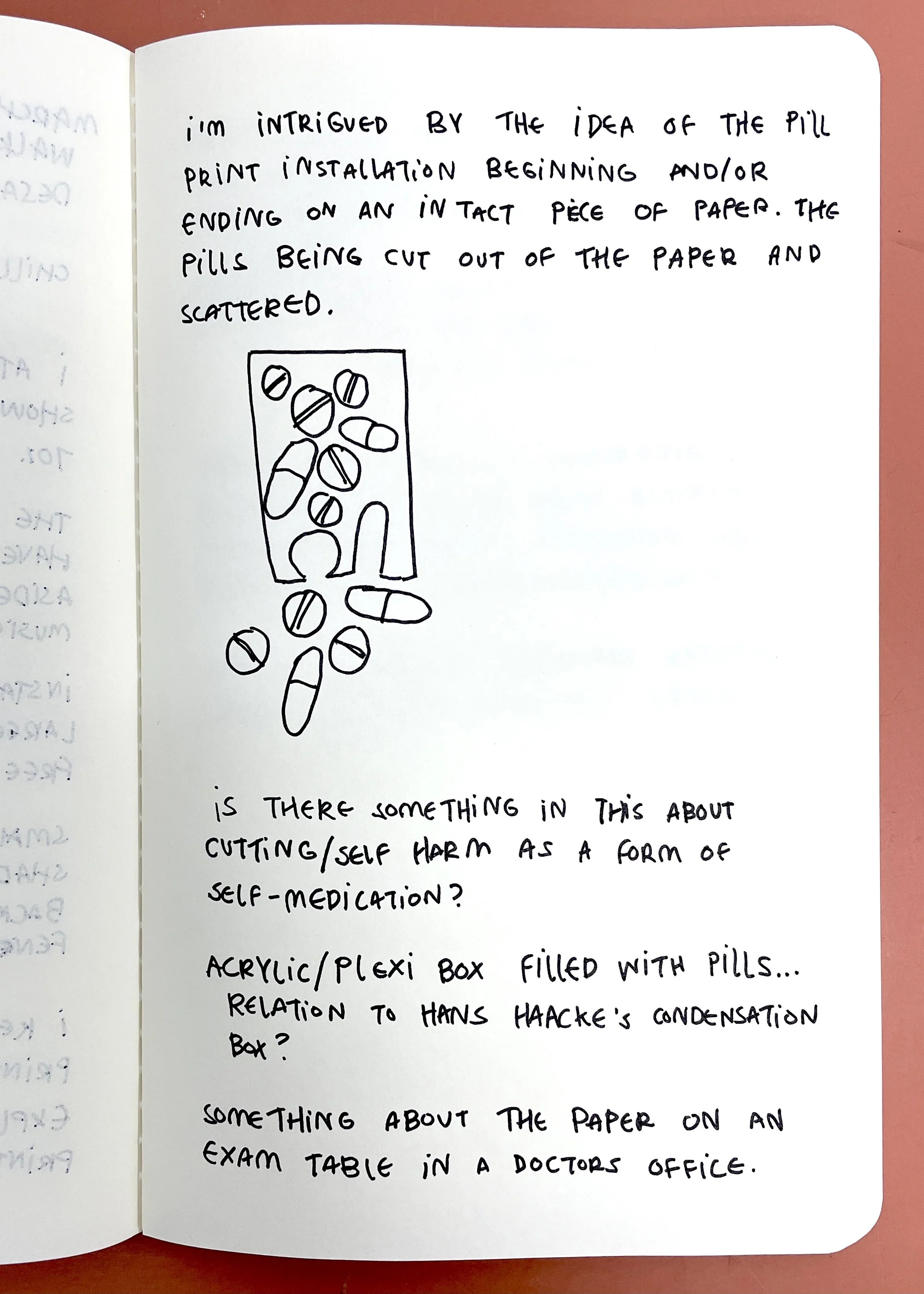

March 21 - Walking Notes

The Intentional Fallacy Fallacy

Intention has been on my mind a lot lately, both in and out of the studio. It’s a topic that often returns to my brain. Outside the studio, my ruminations about intention revolve mostly around language and offense. Inside the studio however, intention takes a different, more ambiguous form.

There is a tension at play when discussing artist intent. On one hand, there’s the idea that artists don’t own the meaning of their work; once a work is put on display for the public, the public’s interpretation of a work is what becomes the meaning of said work. An artist’s job is to make pictures, not to make meaning. I’m paraphrasing both Salts and Kentridge here.

On the other side of the discussion is the idea that an artist’s intention is all that matters. That without artist intent, the work is nothing. That the artist plays the role of sole meaning-maker and author of what a work is about.

There are other thinkers that sit in the middle of this divide. I generally prefer to be in the middle in all things. Nothing is ever black or white. I’m chronically moderate. However, when it comes to artist intent, I find myself swinging back and forth to the extremes on that pendulum, rarely spending much time in the middle.

I like the idea of creating work and confidently putting it out into the world to live and breathe on its own. I have at times made work that didn’t demand one specific reading of the work. I have at time chosen titles that don’t relate to the concept of the work. I have at times made work that doesn’t have a concept at all; whole series with no intention. These pieces are put out into the world with vague ideas attached in the form of titles or series names. And that’s ok. People have talked to me about what they think those works are about. I don’t correct them.

In 2015 a painting of mine wound up on Buzzfeed after being posted to the “mildly infuriating” subreddit. This experience shook me in many ways. I will likely write about that experience more in depth at some point in this journal. For this post, I’ll just focus on the lessons it attempted to teach me about intent. The painting was about social anxiety. It was a low hanging fruit idea, a gray grid on a gray background. One of the squares was slightly misaligned and crooked. The piece was ripped apart in the subreddit feed. What’s important here though, is that very few of the commenters even came close to understanding the intent of the painting. I’d think that the title might have helped this, but the painting was hung in a university sans-title placard.

Why Am I Scared of People In A Room? - 2011, 36” x 48”, latex house paint on canvas

That’s just the thing. Once a work is sold, artists no longer have control over how it is displayed. If the intent of a work is only understood with a title, then the idea resides more in the language of the title than in the work itself. Or maybe the work resides in the combination of the title and the image.

The Buzzfeed painting taught me that I need to be ok letting my art leave my studio without demanding a specific intent. But I can’t do that. I’ve learned over and over that as much as I want to be ok with my intent not being 100% clear for the viewer, I just feel too uneasy with that. There’s something in my practice that doesn’t allow me that freedom. Or I don’t give myself that permission. I’m not sure.

It’s important to distinguish here between when I make work with a clear intent/concept, and when I make work based on aesthetics only.

When my work is about mental health, there’s a little more room to argue for the importance of intent to be attached to the work. When informing the public about suicide or anxiety or self-medication, it’s important that the viewer understand clearly what I’m trying to teach them about. I would imagine it’s the same in other movement-driven art practices, i.e. environmentalism, feminism, politics, etc. You want the viewer to understand your message.

Again, I find myself asking: where does meaning and concept reside? If I make a painting about my struggles with suicide and someone buys it because they think it looks nice, is it still about suicide? Does that meaning stay attached to the work even if the owner doesn’t know it?

What’s my hangup with my non-mental health related work? As I work on this exhibition about my love for the suburbs, I fear that people will see the work as critical of the suburbs rather than a love letter to the suburbs. Does that fear come from a lack of confidence in making my intention clear? Does it come from a fear that people only view the suburbs as a negative space? Does that fear come from a much deeper need to control the way people view me? (I have a feeling it’s all three of these, but mostly the last.)

And don’t even get me started on how this changes with appropriation or curation. Or maybe get me started on that. Perhaps a future post.

I want to explore this more; read Saltz’s view on this, read Monroe Beardsley, read Walter Benn Michaels, read Noel Carroll and W. K. Wimsatt and Steven Knapp. But also, I want to talk to peers and other artists about this. I don’t know how much I value the opinion of critics on this particular topic.

Insignificant Conclusion no. 1

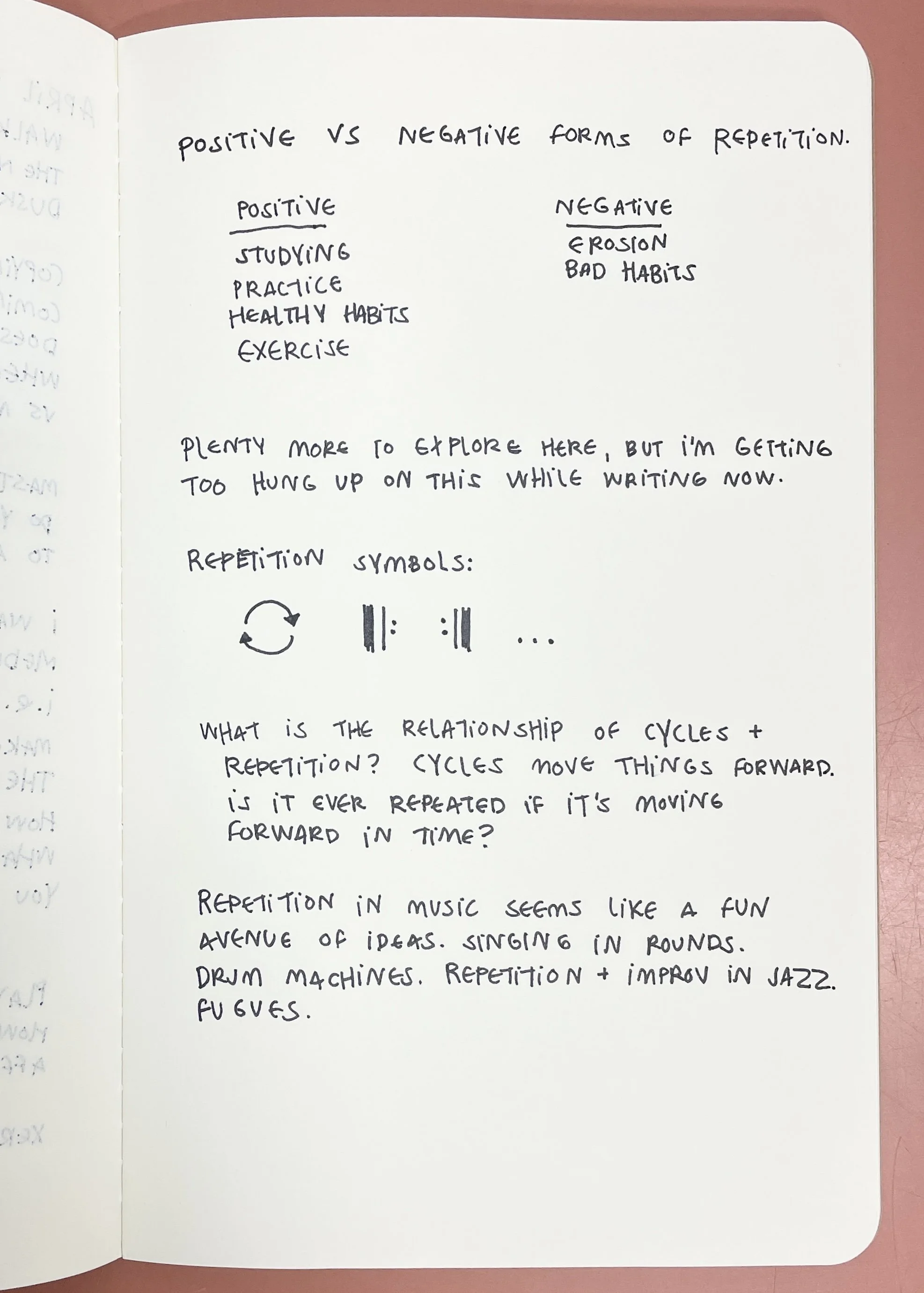

I have spent a good deal of brain function over the last month dedicated to thinking about repetition. I have come to two insignificant conclusions about repetition and my practice:

Repetition is not a new topic on my mind. It has taken up a significant amount of my brain real estate for years and will continue to be so. I am interested in learning how and why I continue to repeat things in my life and in my practice, and why I continue to return to repetition as a tool for ideation.

Understanding repetition as its own noun is deeply challenging. Understanding what repetition is, rather than in relation to my habits seems important and difficult and worth pursuing.

This journal entry will focus on insignificant conclusion no. 1:

Repetition has become a tool for my art practice. Not a skill like color matching in painting or properly wiping an intaglio plate. It is a tool or piece of equipment. It’s the pencil used to render an image. It can be engaged with when the work calls for repetition.

This is both good and bad for my work. It means that I can always use repetition in the process of work. I sits imobile until I choose to mobilize it. Until I choose to include it in my process. It also doen’t change or improve with time the way a skill does. I might get more comfortable using it the way I get more comfortable using a different press for printing, but the press doesn’t change or improve. It’s just there. You become a better printmaker by using the press more, simply by practicing, but the press itself doesn’t change. You make better images, use different processes, wipe your plate better, choose higher quality papers, but the press just remains a tool used for your art which is improving. The same goes for repetition. I think. Maybe.

Frédéric Gros talks about repetition in walking in A Philosophy of Walking. He distinguishes between boredom and monotony. Walking is monotonous.

“When you walk you are going somewhere, in motion, with uniform tread. There is far too much regularity and rhythmic movement in walking to cause boredom, which is fed by vacuous agitation (mind rotating aimlessly in a stationary body)...So it is generally right to contrast walking, which presupposes a purpose, with melancholic wandering.”

I’m not sure how I feel about this. I agree there is a difference in monotony and boredom. But for me, melancholic wandering is often just as productive as walking described by Gros as a way to stave off boredom.

Repetition as it relates to my OCD seems to be important here. I will often go on a walk, purposefully wandering aimlessly and let melancholia take over my mind. Many of my best ideas come from aimless melancholic wandering. But repetition of melancholia can also lead to intrusive thoughts. There is nothing productive for me in intrusive thoughts. There’s a lot to unpack here. I don’t know. It will take time.

I continue to watch the same shows on repeat, listen to the same music, read the same novels, eat the same meals from the same restaurants, etc. etc. This repetition in life acts the same as walking. It keeps my mind occupied with enough mindless stimulation that my brain can focus on other things. On making art usually. I know from unfortunate medication trials that my OCD and my ADD are VERY closely linked. There’s something here about allowing the natural repetition from my OCD to drown out a portion of my racing thoughts so I can focus on what is important at hand.

But this isn’t a PhD in psychoanalyzing and untangling the mess that’s in my head. It’s about researching my creative process. Part two of this journal entry will focus on the larger picture of repetition and how it is/will be a theme in my work rather than just a tool.

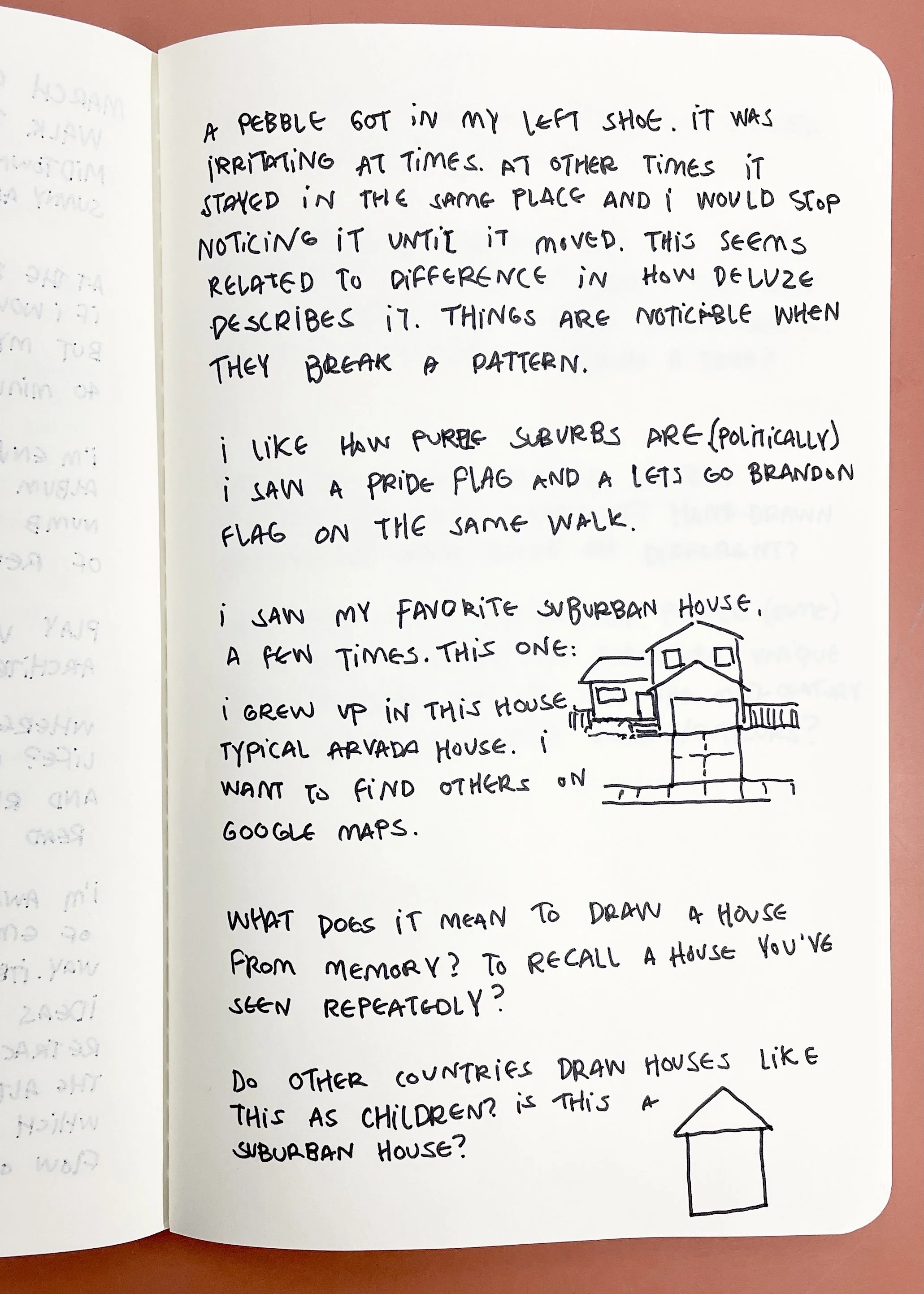

March 5 - Walking Notes

March 4 - Walking Notes

February 2023 Thoughts on Concept and Idea

These are my current inclinations about idea and concept as they stand in February 2023. My relation to idea and concept has a timeline that moves backwards and is one that will continue to evolve and change into the future. This is journal entry is an attempt to capture where I stand in relation to the topic at this point in time.

A portion of this thinking came out of preparation for a workshop for university art students. In the workshop, I taught how to come up with ideas and use concept in their work. I don’t know if this is relevant to this post, but it seems like a detail that I don’t want to forget in the future.

Thoughts on how to interact with and come up with ideas:

Don’t be precious about ideas and concepts.

Research everything of interest.

Follow any paths of curiosity.

Make concept to-do lists.

Talk through ideas with anyone and everyone.

Think about the process and the reasons for process decisions.

Build in time to think.

Engage with a variety of sources and take ideas from them all.

Let yourself misunderstand and misinterpret.

Get to work and let your brain process while you make.

Don’t let an idea go because you think it’s not good.

Sit in the struggle of finding a concept.

Structures I think about to inform my ideation process:

Medium/material

Transitive property (a=b=c . . . a=c)

Cockney rhyming slang

Parable

Wordplay/pun/double entendre

Change the context

Collage/combine

Appropriate (appropriately)

Overthinking these structures:

I don’t know if medium and material are synonyms in this context. I think it can be argued they are the same or different.

Numbers two and three might be the same thing described in different terms. It should be noted that number three comes from Kentridge’s I Am Not Me, the Horse is Not Mine 2008 talk at Tate Modern.

I have struggled finding examples of parables in contemporary art, but I continue to hold onto this as a possible structure of concept. Allegory might be more helpful.

Numbers six, seven, and eight might be the same thing. Or are closely related. Though I think of them each slightly different from the others.

Concept and Idea Linguistics:

I remain very hungup on the language around these topics. What is the difference between concept and idea? We use them interchangeably, but they also sit in different spaces in my head. My inclination is that idea precedes concept, but LeWitt says differently.

From Sentences on Conceptual Art: 9 - The concept and idea are different. The former implies a general direction while the latter is the components. Ideas implement the concept.

For me it’s: THOUGHT>IDEA>CONCEPT>PROCESS>ACTION

Has the etymology of idea and concept changed in the last 54 years? Do we use them differently than we did then? Does this matter to my understanding of ideation in the studio?

I would like to spend time unpacking perceive and conceive in regard to ideation. It feels very straight forward: Perceive is getting an idea from something external (perception). Conceive is to get an idea from our own minds (conception). Maybe. I’d like to be more cognizant of when I get an idea through perception vs. conception. Throughout this journal, I will attempt to consistently and consciously map the trail of my ideation.

I’m ending this journal entry with Olly Moss’s process illustration for his Dirty Harry movie poster. Cause why not?

EOI

Learning How Not to Die: An Interdisciplinary Art Approach to Mental Health

Current research project aims:

How does the choice of medium/material affect the delivery of a concept in my work?

What does the labor of repetition do to a concept when an idea is reproduced in a different medium/material?

How will an interdisciplinary approach to my practice affect how I disseminate academic/scientific mental health data and research to the public?

Project goals:

Through this project, I hope to gain a better understanding of the role of medium/material choice in my studio practice and how that role shifts through repetition. I want to explore the bounds of an interdisciplinary approach to mental health concepts in my work. I also have the goal of growing my practice-based research methods in the studio to better answer other questions present in my practice.

Contextual review:

My research for this project sits at the intersection of exploring the elements of an interdisciplinary art practice and looking at the benefits and damages of different forms of mental health information dissemination. In 2013, Jay Asher published his first novel 13 Reasons Why about a girl who dies by suicide. In the initial years after the novel’s publication, it received mostly positive reviews and was used as a tool for many young people to relate to issues about suicidal ideation. In 2017, Netflix released its original series based on the book. In that same year, the novel became the no. 1 banned book in America after the release of the Netflix adaptation. A study by the National Institute of Mental Health about 13 Reasons Why “found that the rates of suicide for 10- to 17- year-olds was significantly higher in the months of April, June, and December 2017 than were expected based on past data.” (1)

The visual representation of suicide in media entertainment affects viewers in drastically different ways than other forms of suicide portrayal. As an artist who often makes work about suicidal ideation, this situation became a strong point of interest in my studio. While my work is conceptually based, and never shows a visual, violent representation of the act of suicide, I can’t help but think about scenarios like 13 Reasons Why in regard to my own work. I am very interested in how the medium I choose to fulfill a concept changes the viewers perception of such sensitive topics.

While some artists have long considered their practice to be interdisciplinary, there is a greater contemporary rise in practitioners considering their work to be interdisciplinary. In The Interdisciplinary Turn in the Arts and Humanities, William Condee conjectures that this shift to an interdisciplinary approach is due to “a reaction to two problems: the transformation of universities in the twenty-first century and the challenges posed by postmodernism.” (2) As interdisciplinary approaches to studio practices become more common, I am curious how an artist can distinguish where the priorities lie within the various disciplines being interacted with.

For a decade, I have been content to declare that I make drawings or prints or paintings. The broadest I get is to say I’m a 2D artist. But as the themes in my practice have expanded, I have arrived at a place where I now question if 2D artifacts are the most effective way of disseminating my ideas and what happens when I combine 2D mediums with other art-making approaches.

(1) Release of “13 Reasons Why” Associated with Increase in Youth Suicide Rates. (2019, April 29). National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). https://www.nimh.nih.gov/news/science-news/2019/release-of-13-reasons-why-associated-with-increase-in-youth-suicide-rates

(2) Condee, William. “The Interdisciplinary Turn in the Arts and Humanities.” Issues in Interdisciplinary Studies, no. 34, 2016.

Methods:

Data Collection: My work in the studio always begins with mental health research. This data collection resides in three areas; reflecting on my own experience with the mental health struggle, reading and analyzing qualitative and quantitative data from the mental health research field, and engaging with works of humanities around that mental health topic, i.e. novels, movies, music, art, etc. This data collection provides me with the foundation needed to build concepts from which to work. While my projects always begin at this step, this data collection will continue throughout the whole project.

Repeated Body of Work no. 1: The first experiment as a research method in my project will be producing and repeating a body of work on one specific mental health struggle. The series will be produced in its entirety before moving on to the second, repeating body of work. I will then produce a second series about the same mental health struggle but in a different medium. If the experiment warrants it, I will produce a third body of work again, repeating the mental health struggle through a third lens.

Repeated Body of Work no. 2: The second experiment in the project will be similar to the first, but rather than completing each series in its entirety, I will produce individual works on the same mental health struggle in different mediums simultaneously. While the works being produced will be contemporary to one another, they will be kept in separate bodies of work in order to see how the conversation in process affects the work in the end.

Reflective Analysis: Throughout the whole project, I will engage in self-reflective analysis of the research project. Up to this point, my reflective analysis has been done mentally, and usually at the end of a series. In this project, the reflective analysis will take a more active and consistent role through diligent journaling and documentation in the studio.

Viewer Feedback: I will conduct a survey of reactions to the different bodies of work. Because my practice heavily involves audience reaction to ideas presented, it is important for me to learn from the viewer how they react to the material/medium choices in regard to the concepts and themes in the work. The surveys will comprise of two groups:

A group of individuals who share the mental health struggle presented in the work will be surveyed about their relation to the work and which bodies of work led to more tangible takeaways for the viewer.

A separate group of individuals who don’t have the mental health struggle will be surveyed about the understanding and empathy gained through the various bodies of work presented.

Timeline/structure:

The first six months of the project will be spent conducting initial data collection and exploring concepts and themes for the two main experiments. By the end of the six months, I will have a firm foundation for the mental health struggles that will be explored in the second phase of the project. Possible themes for the bodies of work are: self-medication, suicidal ideation, depression, anxiety, and body image.

I will begin building the first body of work in month six of the project and will continue to produce work in the studio for two years. The two repeated bodies of work experiments will be conducted in this two-year time span, with one year dedicated to the first process and the second year dedicated to the second process.

For the last six months of the project, I will conduct feedback from viewers of the work. I will also compare this feedback with my own self-reflective analysis during this last stage of the project, which will let me complete the project with a cohesive thesis about my findings.

Indicative bibliography:

Bárbara Rodríguez Muñoz. Health. London, Whitechapel Gallery ; Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2020.

Condee, William. “The Interdisciplinary Turn in the Arts and Humanities.” Issues in Interdisciplinary Studies, no.

34, 2016.

Foucault, Michel. Madness and Civilization. Vintage, 30 Jan. 2013.

Gilles Deleuze, and Paul Patton. Difference and Repetition. New York, Columbia University Press, 1994.

Graham, George. The Disordered Mind. Routledge, 2013.

Holmes EA, Crane C, Fennell MJ, Williams JM. Imagery about suicide in depression--"Flash-forwards"? J

Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2007 Dec;38(4):423-34. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2007.10.004. Epub 2007 Oct 13.

PMID: 18037390; PMCID: PMC2808471.

Kentridge, William. Six Drawing Lessons. Harvard University Press, 2014.

Kierkegaard, Soren, Howard Vincent, and Edna Hatlestad Hong. Fear and Trembling ; Repetition /. Princeton,

N.J., Princeton University Press, 1983.

King, Scott. Anxiety & Depression : Climb out of the Cellar of Your Mind... Zurich, Jrp Ringier, 2009.

Lange-Berndt, Petra. Materiality. London, Whitechapel Gallery ; Cambridge (Mass.) ; London, 2015.

Advisory team support:

The team I am interested in working was chosen based on their versatile and sensitive approaches to art-making. Because I work with such sensitive topics, often drawing upon my own experiences, support along the way is immensely helpful. I’m not looking for therapy through my advisory team, but an understanding and support of the sensitive nature of my themes is important to me. I also value critique and want to push my practice based on honest and transparent feedback from professionals I respect. And lastly, I need guidance on how to hone my practice-based research in the studio in a more formal way.